‘Photography and the Civil War’ on display at NOMA

25th February 2014 · 0 Comments

By Fritz Esker

Contributing Writer

The New Orleans Museum of Art recently unveiled “Photography and the American Civil War,” a touring exhibition of over 200 Civil War photographs on display through May 4th.

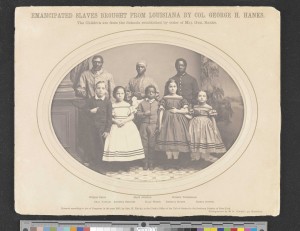

The photographs cover a wide range of people and situations within the Civil War. While photography was roughly 20 years old when the battles began, it did not become accessible to many people until the onset of the Civil War. As a result, it is the first time in American history when people of all races and social classes were photographed.

It was common for soldiers on both sides to have their portraits taken after enlistment. A copy would be given to loved ones to be kept in lockets or other keepsakes that loved ones would keep on their person.

“It was a way of keeping them (the soldiers) close,” said Russell Lord, curator of photographs at NOMA.

For the soldiers themselves, the portraits served as a form of self-preservation. They were afraid they would not return from the battlefields and wanted something of themselves to remain should they die.

Included are photos depicting the lives and experiences of African Americans during the Civil War. Photos recalling both the torture and the triumph of African Americans are prominently displayed in the exhibit. One eye-catching photo on display is that of a whipped slave who had escaped his plantation to an encampment of Union troops. A picture of Sojourner Truth that was taken in 1864, reproduced, and sold to help fund Truth’s work with the Underground Railroad is also featured. Truth’s statement about the sale of these photos was, “I sell the shadow to support the substance.”

The exhibit also depicts the work of African Americans in the Union Army. There’s a photograph of the Corps d’Afrique, a.k.a. the United States Colored Troops, first recruited into military service during the Civil War (by war’s end, there were 175 USCT regiments).

Even pictures of buildings in the exhibit convey the plight of the era’s African Americans. One such photo is of a structure that housed a slave dealership. Before and during the war, slaves would be shackled inside and sold. Once Union troops seized it, it became a prison for Confederate soldiers.

These photos, and others, confirm that photography in the Civil War was often used for the purposes of conveying a message viscerally to an audience, whether it was a whipped slave depicting the cruelty of slavery, or a dead soldier on the battlefield illuminating the barbarism of war.

The exhibit features many battlefield photos by renowned photographer Alexander Gardner. While Gardner was present for the Battle of Antietam, all photos are either before or after the battle took place. Because the chemistry was so slow and exposure times were so long, any action photos would have come out as a giant blur.

While battlefield photos were used to convey the brutality of the opposing side (be it North or South), some of the era’s photos were used to humanize. Abraham Lincoln’s photograph was prominently used in his campaign materials in 1860 (a ribbon with Lincoln’s photo can be seen in the exhibit).

Photos were also used in the era to convey information. After Lincoln’s assassination, photos of John Wilkes Booth and other conspirators were widely distributed in one of the first wanted posters. The exhibition devotes an entire room to photos by Reed Bontecou depicting the medical side of the war. Bontecou took portraits of wounded soldiers about to undergo primitive surgery and portraits of soldiers who had just underwent surgery to educate other doctors. This part of the exhibit is set off to the side so squeamish patrons can bypass it.

Not all of the exhibits are pictures. Legendary photographer Matthew Brady’s actual camera (not a reproduction) is available for viewing so patrons can get a sense of how cumbersome early cameras were.

The exhibition’s original home is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Jeff Rosenheim, the curator of the exhibit at the Met, began work on it 10 years ago. He was drawn to the fact that photography was such a young medium at the time and that it was used to capture so many issues of identity and self-destiny during the conflict. A former Tulane grad student, Rosenheim has ties to New Orleans and wanted locals to have a chance to see the exhibition.

“It was very important to me that the show travel south of the Mason-Dixon line,” Rosenheim said.

A few photos from local and regional donors were added to supplement the show at NOMA. A Florida-based donor lent a series of photographs depicting the hanging of the conspirators in the Lincoln assassination. Tina Freeman, a New Orleans collector, lent several pictures by George Barnard showing the after-effects of General Sherman’s march.

“We are able to present a very full version of the show thanks to the generosity of local collectors,” Lord said.

NOMA is the last stop on the exhibition’s tour. Once its time in New Orleans ends, the photos will be shipped back to New York and placed in storage. Because the pictures are very light sensitive, they cannot be displayed often.

“It’s really a once in a lifetime experience,” Lord said.

This article originally published in the February 24, 2014 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.