Rev. Avery Alexander statute to be put back on display in Spring, says state

2nd September 2014 · 0 Comments

By Susan Buchanan

Contributing Writer

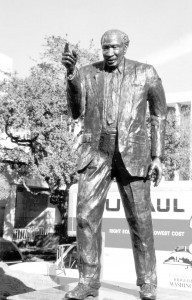

After being confined to a crate at New Orleans Lakefront Airport for the last five years, a bronze statue of civil rights leader Avery C. Alexander will be erected in front of the new University Medical Center at Galvez and Canal Streets by next spring, according to the state’s Division of Administration. The eight-foot statue, called “The Crusader,” was pulled out of storage and cleaned early this year, and is being outfitted with a new base. “The statue will be installed when the hospital’s construction is complete and before it opens sometime in the spring,” DOA spokesman Gregory Dupuis said last week. In 2012, the state legislature named the center after Alexander, a Baptist minister and former state representative, who died in 1999.

But none of that’s happening fast enough for Bring Back the Avery Alexander Statue Committee. The group’s members demonstrated in front of State Senator Karen Carter Peterson’s office on O.C. Haley Boulevard last Wednesday and delivered a letter to her, seeking the statue’s return to Duncan Plaza—where it originally stood. Democratic Senator Peterson authored the 2012 bill naming the medical center after Alexander.

The state-commissioned statue, sculpted by Sheleen Jones of New Orleans East, was installed in Duncan Plaza in 2002 but removed when the Louisiana Supreme Court and an office building were demolished in September 2009 because of Katrina-damaged basements. At the time, the sculpture’s removal was intended to be temporary, Mike Howells of Bring Back the Avery Alexander Statue Committee said last week.

“Lots of people have asked about the statue, and the state’s been looking for a place to put it,” Jones said last week. “It has to be on state grounds. There was some talk about Poydras Street.”

But Algiers resident Eloise Williams, a civil rights activist who worked with Avery Alexander, doubts Poydras was ever under serious consideration. “Business leaders and politicians don’t want the statue there, reminding them of the city’s racist past,” Williams said Wednesday. Poydras Street is home to oil-and-gas company offices and financial institutions at one end and the Mercedes-Benz Superdome on the other. “Avery Alexander’s struggles don’t fit in with Governor Jindal’s image of the way he wants the world to be,” Williams said.

Jones said her sculpture, when it was in Duncan Plaza, pointed at City Hall, where police on Oct. 31, 1963 dragged Alexander from a sit-in at the building’s segregated lunch counter. “He was pulled by his heels up two flights of stairs and across the sidewalk to a paddy wagon,” she said. “The statue pointed back at City Hall for that injustice, which could happen to any person of color at any time.” Jones used Alexander’s shoes in her work, along with family photos of his clothing. “On the sculpture’s coat lapel is a ribbon, which symbolizes sensitivity to human rights in addition to breast cancer awareness,” she said. Jones produced the bronze statue in three months, starting with a clay mold and making a cast in a lost-wax process.

Howells said statues are always significant symbols, and he questioned why Alexander’s has been out of sight for so long when monuments to slave owners and segregationists and the Battle of Liberty Place obelisk, dating to1891, are plainly in view. As a French Quarter resident, he’s unhappy that the Liberty Place or “White League” obelisk—removed from Canal Street in 1989 when the Canal Place shopping mall was built—was re-erected near the aquarium on Iberville Street in the Quarter.

Not only was the 20-foot White League obelisk resurrected after four years in storage but at the March 3, 1993 re-dedication ceremony, Avery Alexander—by then an 82-year-old state representative—was put in a choke-hold by the police and arrested at the event, said Howells, who was there. David Duke, a former grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan and a Louisiana state representative, spoke at the ceremony.

As for the Battle of Liberty Place, the Crescent City White League, made up of white men—some of whom were Confederate veterans—outnumbered and overpowered city police and the militia of the state’s biracial Reconstruction government on Sept. 14, 1874. The battle has been commemorated by white supremacists since then.

These days, when everyone outdoors seems to be staring at a cell phone, people still notice monuments. In March 2012, the Liberty Place obelisk was spray-painted with the name Wendell Allen, a Black youth killed by a New Orleans policeman that March. And the same month, the Jefferson Davis sculpture on South Jefferson Davis Parkway and Canal Street was sprayed with the name of Justin Sipp, who was killed by police in Mid-City. At the time, the Robert E. Lee statue in Lee Circle was painted with the name Trayvon Martin, killed by a neighborhood watch leader in Florida in February 2012.

Avery Alexander’s sculpture was cleaned this year by New Orleans volunteer group Monumental Task Committee, Inc., which also provided advice on a new pedestal. “The statue will make an impressive entrance to the medical center,” Pierre McGraw, president of Monumental Task, said last week. “But first, the hospital has to complete the ground to put it on.” His group is devoted to preserving the city’s 245 monuments, with the help of students, the Boy Scouts of America and members of the military from Federal City in Algiers. Monumental Task plans to develop a digital guide that will map statues around town soon.

Dupuis of DOA said any costs associated with erecting Alexander’s statue, beyond the volunteers’ cleaning, will be covered by the university hospital’s construction budget.

Alexander’s sculpture is mentioned in “Song for New Orleans,” a poem published by Texan Carol Coffee Reposa in 2009 about what 19th century poet Walt Whitman would have seen here in the last decade. “Under a starry night, he would watch the endless pageants of streaming lights to find his way to Duncan Plaza, where Avery Alexander points the way, leaning into civil rights,” Reposa wrote.

Other sculptures by Sheleen Jones include civil rights lawyer A.P. Tureaud, erected in 1997 at the park at the corner of St. Bernard and A.P. Tureaud Avenues. Her statue of Big Chief Allison “Tootie” Montana, a civic leader, was installed in Armstrong Park in 2010. And her new “Healing Tree” sculpture was dedicated at New Orleans East Hospital in August.

After Alexander’s death in 1999, the Louisiana Senate paid tribute to him with Act 1234, creating the Reverend Avery C. Alexander Plaza on land bounded by Gravier Street, the Lake Ponchartrain Expressway, and Claiborne and Loyola Avenues. Act 1258 renamed Charity Hospital in New Orleans after the civil rights leader. In addition, the McDonogh No. 39 School on Saint Roch Avenue was named for Alexander in 1999. And in 2011, Occupy NOLA activists referred to Duncan Plaza as Avery Alexander Plaza.

This article originally published in the September 1, 2014 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.