Library of Congress hosts Civil Rights exhibit

22nd September 2014 · 0 Comments

By Jazelle Hunt

NNPA Washington Correspondent

WASHINGTON (NNPA) – In honor of the 50th anniversary of the landmark Civil Rights Act, the Library of Congress has launched “The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom,” an exhibition of rarely seen documents and oral histories on the push for civil rights.

A few things set this exhibition apart from the multitude of this year’s commemorations.

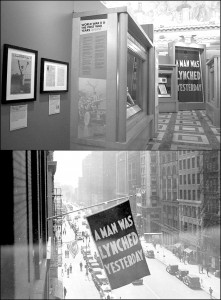

The Library draws from its exclusive archives of the NAACP, the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, James Forman of SNCC, the recently borrowed Rosa Parks’ papers, and more. Visitors will see more than 200 noteworthy letters, photos, drawings, artifacts, and more, such as a page from Ralph Ellison’s draft of Invisible Man; a telegram from A. Philip Randolph to Paul Robeson discussing the lynching of Emmett Till; and the NAACP’s lynching awareness flag, which hasn’t been showcased in nearly 15 years.

The Library draws from its exclusive archives of the NAACP, the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, James Forman of SNCC, the recently borrowed Rosa Parks’ papers, and more. Visitors will see more than 200 noteworthy letters, photos, drawings, artifacts, and more, such as a page from Ralph Ellison’s draft of Invisible Man; a telegram from A. Philip Randolph to Paul Robeson discussing the lynching of Emmett Till; and the NAACP’s lynching awareness flag, which hasn’t been showcased in nearly 15 years.

According to the directors, this exhibit is also unusual for the library. It has more audio/visual media than any other exhibit has had before, and it’s the first time that media has been interactive in a temporary exhibit. Temporary Library of Congress exhibits usually run three to six months – this one will run a year.

By all accounts, every feature has been painstakingly chosen. Even the exhibit’s color scheme is inspired by the cover art of the iconic 1959 album, Mingus Ah Um by outspoken jazz artist and activist, Charles Mingus. (The album is one of 400 recordings preserved in the Library for posterity). Many of the items on display have a personal touch to them – there’s the founding document for the Southern Christian Leadership Council, typed and signed by Bayard Rustin, singed by what one could guess were his falling cigarette ashes. There’s a draft of the speech John Lewis, then-chairman of SNCC, was to deliver at the March on Washington — typed-up and peppered with proofreading marks from veteran Civil Rights leaders who toned down his language. One page is typed on the back of an itinerary for the day.

“You go through a folder or a box with as many as 30 documents, potentially hundreds of pages. You have no idea what you’ll find. It’s a treasure hunt,” says Adrienne Cannon, African-American history and culture specialist for the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. Cannon unearthed and handpicked many of the documents on display.

“We want to be able to make connections. If we introduce something in the 1940s it’s like taking a needle, making a stitch, picking up the thread and 20 years later making another stitch or needlepoint that connects the two. Generally, that’s the way history works, all these connections.”

But what truly distinguishes the Library of Congress’ exhibition is that it ventures well beyond stock narratives of sit-ins and Freedom Rides.

“One thing that’s different about this exhibit is…that it goes beyond being an exhibit purely about the Civil Rights Movement,” says Betsy Nahum-Miller, senior exhibition director. “It shows what went into getting this piece of legislation passed and how long back that effort goes.”

The exhibit begins in the late 1800s with a prologue on abolitionism, emancipation, the Reconstruction period, and the first Black statesmen. Next, it explores segregation and the rise of legal strategies and grassroots groups, then WWII and the post-war years, when other oppressed groups began to agitate. Next, visitors explore the Civil Rights Movement and the passage of the 1964 bill. The last section explores the impact of the law.

“We’re showing petitions against slavery, the denial of civil rights and that struggle for freedom – through the law, through individuals who took the chance of lobbying, through grassroots organizations, and through the three branches of government,” says Carroll Johnson-Welsh, senior exhibition director. “The exhibition shows that as you walk through. We only have a small amount of space, but we’ve managed to show all these aspects.”

Visitors will learn about lesser-known key moments such as the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and the NAACP’s campaign for a permanent Fair Employment Practices Commission (a precursor to today’s Equal Employment Opportunity Commission).

They will also see contributions from Black women, international leaders, and non-Black people of color, via unsung figures such as Anna Arnold Hedgeman, Tom Mboya, and then-Rep. Patsy Takemoto Mink (D-Hawaii). Other marginalized groups who suffered under segregation and Jim Crow are accounted for as well.

“While we interpret the beginning of the Civil Rights Act as rooted in the struggle of African Americans to secure basic civil rights in this country, we didn’t want to make the exhibit simply about African Americans, because this act encompasses all Americans,” Cannon says.

Although this broad view of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is maintained, a rotunda depicting the days of political maneuvering leading up to and including the law’s passage is the heart of the exhibit. Through excited correspondence between Clarence Mitchell, director of the Washington Bureau of the NAACP, and Roy Wilkins, NAACP chief executive, visitors get a play-by-play on the introduction, attempted defeat, and landmark passage of the law. There’s even the teleprompter transcript President Lyndon B. Johnson read as he signed the legislation.

The exhibit ends with a corridor panel detailing the 11 titles, or sections, of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 – how the law has withstood time and legal tests, and how it serves as the basis of similar laws for other marginalized groups. Library officials hope to inspire a new generation to safeguard and advance the cause of American civil rights.

“I hope that even if they didn’t go through the exhibit…that they see those titles and understand the importance of what the Civil Rights Act is and what rights it affords,” Johnson-Welsh says. “We hope when people leave the exhibit they realize that there’s a lot of work still to be done.

This article originally published in the September 22, 2014 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.