Before Jazz Fest, there was the Afro-American Arts Festival

20th April 2015 · 0 Comments

By Michael Patrick Welch

Contributing Writer

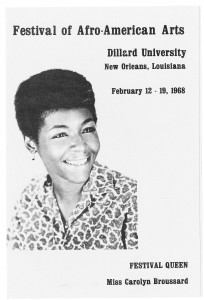

Beginning in February 1968, before “Negro History Week” eventually became Black History Month, the Dillard University group African Americans for Progress helmed the “Afro-American Arts Festival,” featuring various well-known and underground Black artists of all different mediums and genres. Some say Dillard’s AAA event inspired the Jazz and Heritage Fest, founded in 1970.

“I don’t think it’s a coincidence,” says John Kennedy, the Assistant Archivist at Dillard who, fascinated by the AAA festival and why it went extinct, dug up yearbooks detailing the annual event. “It was basically the same thing Jazz Fest is now. It was a wide range of famous people from actors to singers, the prominent poets and cooks of that time. There wasn’t another major arts festival that drew in prominent Black artists of all types.”

Carl Baloney, now a mortician in LaPlace, was a founding member of African Americans for progress in 1967. “I remember during college, we were mandated to go to church, and then after church they’d have entertainment for us, all paid by the Lyceum board. They’d have us watching some glee club or something from the North East, about 20 white boys trying to sing negro spirituals! We were like, ‘What the hell? This is our money being wasted. We need to bring in artists that represent us. Why can’t we get someone like Cannonball Adderly?’ We brought in everyone from Amiri Baraka, LeRoi Jones IV, Maulana Karenga who started Kwanzaa. We had local artists too: Earl Turbinton, Lady BJ, Tambourine and Fan was there with the Indians, and Danny Barker led a second-line around the campus.”

An announcement of the first Afro-American Arts Fest in 1968 states:

“The kickoff day will be devoted to an exploration of Negro music: Both a workshop and an exhibition of African dancing staged by two Xavier University students from Africa…An exploration of Negro blues gospel and folk music will be on Tuesday’s agenda…. Literature, graphic arts, cinema, African dances, pays and Afro-American history will highlight the third, fourth and fifth days.

John Killens, author or Black Man’s Burden, will conduct a workshop on literature. Other workshop participants will include Tom Dent and Eluard A. Burt Jr., director and director of workshop respectively, Free Southern Theatre, Vernon Winslow, assistant professor of art at Dillard and Edwin B. Hogan, head of the music department at McDonogh 35 High School. [Dillard’s] Theatre Guild… will stage “Hand on the Gate” by Roscoe Brown and “Malik,” an original [play] by Dillard graduate Norbert R. Davidson Jr. The New World Theatre will present “The Dutchman,” a controversial play by Leroi Jones. Thursday and Friday are showings of two movies. Black Orpheus and The Sound of Drums.

A workshop on New Orleans jazz traditions will be held Saturday afternoon, followed by a mock funeral featuring a New Orleans second-line band. Alto saxophone players Julian “Cannonball” Adderley Quintet will headline the Festival Saturday night.”

The academic paper, “Within These Walls” (a history of Dillard by Louise Rernard and Radiclani Clytus), explains that the Afro-American Arts Festival was started by Morehouse graduate Albert W. Dent, Dillard’s president between 1941 and 1969. Along with helping found the United Negro College Fund, and creating or renovating 75-percent of Dillard’s current campus, “Dent promoted events that served to shape an emerging new black identity,” write the paper’s authors.

“I wouldn’t say Dent started the festival,” says Dr. Henry Lacey, who worked at Dillard during that time as both a literature teacher and eventually as Vice President of academic affairs. “I didn’t have a role [in the fest]. Not many faculty members had a role in it, period. That was one of the things we marveled at: Our students were take-charge guys and gals. The students had that thing in hand! Particularly the writers who were invited, they wouldn’t have been administration favorites by any means,” Lacey chuckles.

The short-lived Afro-American Arts Festival served many purposes.

“There was not much Civil Rights involvement from Dillard during that day, the way there had been at other universities. And we felt like we should have been a part of it,” remembers Baloney of his group’s intentions at the time. “We also put on that festival just to connect us to the rest of the city of New Orleans, because the students considered Dillard to be an island—you can be on the campus and not know what’s going on in the outside world. We hosted something on campus every day during that week, but then also something in the clubs every night, as well as in the churches, in the parks, with everything culminating on campus. At the end of Tulane Avenue we’d have our own little Jazz Fest—it was a carbon copy. It’s amazing to look at Jazz Fest today; that’s us, that’s what we did, in a nutshell.”

Dr. Lacey, who also sits on the Jazz and Heritage honor council since retiring from its main board, sees some similarities between the AAA fest and what today we call Jazz Fest. “I think its influence on the Jazz Fest may be exaggerated,” he admits, “but I think its influence did show. AAA fest showed that there was an audience for contemporary jazz. I don’t think a lot of modern jazz was coming to town when we had Max Roach and Abby Lincoln at our festival. That year had a good mix of R&B, with the Friends of Distinction too, all on the same bill at the gymnasium. It really cut across genres. The idea of bringing all kinds of music together in the same venue may have come from Dillard; it was unheard of at the time.”

The Afro-American Arts Festival also featured Black theatre productions, visual art, and a large roster of independently made Black films. But it wasn’t just about entertainment. “You had your music, vendors, local artists, but it was all developed so the community could get a better idea of the Africa diaspora as well,” says John Kennedy. Or as Dillard’s yearbook put it at the time, the festival was, “relating it more to activism than shallow entertainment” as it was designed to “provide a medium through which Black people could become more aware of their heritage.”

Kennedy says it’s done that for him.

“As a native of New Orleans, that was nothing I was ever taught,” he says of Dillard’s nearly forgotten cultural celebration. “I only learned about this when I started working at my alma mater Dillard this October. The fest’s history has begun to matriculate more but it is something that needs to be taught more often.” For this same reason, Kennedy helped make the long-gone festival a centerpiece in Dillard’s Black History Month events.

“I created pamphlets containing the facts and we discussed it during a forum, centered around the documentary “Hidden Colors.” We urged students to discover more about their University,” says Kennedy, hoping his efforts might drum up student interest to re-start the event.

Until then, Kennedy has been trying to pinpoint when and why the fest burned out and faded away. Dr. Lacey doesn’t know either. “Our class was just a particularly progressive group of young people with a common cause,” guesses Baloney. “Probably when that dynamic group of students left, complacency set in and it died out.”

Baloney says the core members of African Americans for Progress still get together during holidays. These nostalgic dinner parties are all that is left of a once proud African-American collegiate tradition.

This article originally published in the April 20, 2015 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.