The Little Rock Nine remembers

2nd October 2017 · 0 Comments

By Sarafina Wright

Contributing Writer

(Special from The Washington Informer) – The National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) closed out the celebration of its one-year anniversary with surviving members of the Little Rock Nine who courageously integrated a high school 60 years ago despite harassment and threats of violence.

The “Reflections of the Little Rock Nine” took place on Tuesday, Sept. 26, one day after the 60th anniversary, where a group of Black teenagers broke the color wall at a hostile, all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Ark.

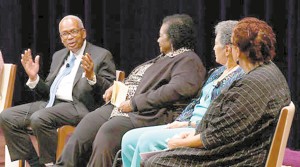

Surviving members of the Little Rock Nine, who integrated an all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Ark., 60 years ago, reflect on their courageous act at the National Museum of African American History and Culture on Sept. 26.

“The integration of Central High School was an event that transfixed and transformed the nation,” he said. “It reminds us of the collective courage it takes to change the nation. That moment was a clarion moment that demanded that America live up to its ideals and its laws.”

Melba Patillo Beals, 75, asserted that the courage to integrate Central High School started at the age of four when she realized the conditions of African Americans in Little Rock.

“At four years of age I was waiting for the stork to come get me because that’s just how much I disliked Little Rock,” Beals said.

“I watched my parents go from proud, really strong people inside the house and at church, but when we went to the local grocery store or anywhere outside of our tiny Black vineyard they became humbled, frightened, really sad people.”

“‘Yes, ma’am we know our place’ were the answers they gave white people. If we stood in line to buy groceries and a white lady came up, we had to step aside. So, the basics of my early life were a prelude of why I wanted to leave,” she said. “I saw and understood by the time I was 14 that education was my only way out. It was the only train smoking for me to get out of there.”

Civil Rights Takes a Front Seat

Ernest Green said that his motivation came from a more provocative place. He wanted in on the burgeoning civil rights movement growing in the country.

“I was excited about the things going on around us,” he said. “Little Rock was after the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Dr. King hadn’t ascended yet, but his work was beginning to be seen and this was also not too long after Jackie Robinson’s breakthrough into baseball.”

“More importantly for me I was motivated by the pictures in JET of Emmett Till’s murder. That made a real impression on me.”

Green felt that change was indeed on its way especially after the landmark decision of Brown v. the Board of Education that declared ‘Separate but Equal’ unconstitutional.

“When the ’54 decision was handed down, I’ll never forget that the next day the local paper said the decision was going to change the face of the South and I said good!”

“For me the face of the South ought to be changed and I wasn’t sure what role I was going to play, but we all found ourselves taking part in a piece of history,” he said.

“I never thought 60 years later I’d still be talking about getting out of high school.”

Green the first Black graduate of Central High School, also dubbed the leader of the Little Rock Nine, had a special guest at his graduation in 1958.

“It turned out unbeknownst to me that Dr. King had been speaking in Pine Bluff, not far from Little Rock and he was close to Reverend Ogden and Mrs. Bates the president of the Arkansas NAACP,” he said.

“At the end of the ceremony I walked up and Dr. King was sitting with my family and my mother.”

Green doesn’t remember what they talked about claiming that at 16 you don’t want to have conversation with an adult.

“However, my mother kept a diary of the gifts that I got,” he said. “And in that diary, it’s a notation that said M.L. King, from Montgomery, Alabama, and a $15 check. I’m one of the few living Americans who can say Martin Luther King attended his high school graduation.”

Kinshasha Holman Conwill, deputy director of NMAAHC, reviewed the sequence of events that led to Black teenaged students taking on the Arkansas white power structure.

“Before the fateful day of September 25, Governor Orval Faubus ordered the Arkansas National Guard to halt the efforts of these nine students from entering Central High,” she said.

“Members of the Little Rock Nine attempted twice to gain entrance and were blocked each time by state guards and a bigoted and intolerant community that taunted them with racist epithets and viciousness.”

“Yet and still they rose. They entered on Sept. after President Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered 1,200 paratroopers to escort them.”

Beals contended that none of the nine members foresaw the mobs that would await them as they tried to enter their new school.

“None of us expected the mobs or the calling of the National Guard. You can’t prepare for something when you’re the first,” she said. “I was chased down the street with ropes and I’m thinking to myself for the first time in my life about death. Our parents weren’t there and the police weren’t going to help us.”

But things inside the school didn’t get much better for the Little Rock Nine.

“The white students were running all over the place, they broke glass and put it in the shower in the gym, they kicked people down the stairs, they stepped on the back of our heels,” Elizabeth Eckford said.

Beals echoed her statement recalling the times she found herself cornered in the bathroom.

“Even though we had bodyguards for a time they could not follow us into the girls’ bathroom,” she said. “They would light notebook paper on fire and throw it over the stall.”

Economics Used to Stall the Movement

According to the accounts of the surviving members of the nine including Minnijean Brown Trickery, Gloria Karlmark, Carlotta Walls Lanier, Terrence Roberts, Thelma Mothershed Wair and the deceased Jefferson Thomas, not only did they suffer, but the entire Black community in Little Rock did too.

“Our parents put house notes, car payments all of that on the line because they thought for a better vision for the future,” Green said. “They suffered, they lost jobs and I know they lost sleep.”

Beals said that the segregationists in the city tried to economically choke the Black community in retribution for the nine attending Central High School.

“There was an enormous impact on the entire community,” she said. “Many Black people suffered — many lost their jobs.”

Ironically, some Black families survived due to the donations of wealthy whites Beals noted.

Sixty years later, the remaining Little Rock Nine still desire to be on the front lines of the right side of history.

“Keep going. Why would you stop? You think you home now? When you stop, you slide backwards like we’re doing today,” Beals told the audience. “How do I feel about the KKK marching? How do I feel about white supremacy taking center stage once again? I feel like I got to get up again at 75 years of age and get rolling. Find a motorcycle, find a walker, whatever, but we can’t sit down, we can’t let go. Not now.”

This article originally published in the October 2, 2017 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.