Black soldiers played key roles in World War I

19th November 2018 · 0 Comments

By Frederick H. Lowe

Contributing Writer

(BlackmansStreet.Today) — World leaders met Nov. 11 in Paris to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I, a conflict during which thousands of American black men fought because they strongly believed it would lead to racial equality in United States, a radical idea first advanced by W.E.B. DuBois, an intellectual, activist, and editor of Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP.

“First your country, then your rights,” DuBois wrote in Crisis.

But what the soldiers experienced when they returned to the U.S. following the war was decidedly mixed.

The war began on July 28, 1914 and ended with an Armistice, signed on November 11, 1918.

The United Kingdom, France, Germany, Austria, Hungary, The Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria fought in the war, which was ignited by the assassination in Sarajevo of Franz Ferdinand, the archduke of Austria-Hungary, on June 24,1914.

Russia, the United Kingdom and France were allies during the war. The United States did not officially enter the war until April 1917.

Some 350, 000 Black-American soldiers fought for France, which was suffering a shortage of fighting men. There also were Blacks from Africa and East Indians from India who fought for France and Britain, the countries’ colonial masters, during World War I.

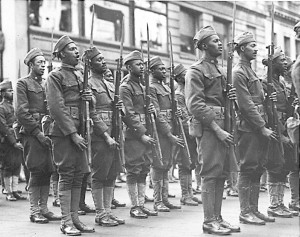

The 369th Infantry Regiment, later known as the Harlem Hell Fighters, was the first African-American regiment to fight in World War I. The regiment shipped out at the end of 1917 and came under the command of the French Army. The men of the 369th were issued French helmets and weapons and sent into combat.

They quickly established a reputation for courage and effectiveness. During 191 days of combat, they never lost ground or had a man taken prisoner. At the end of the war, the 369th was the first Allied unit to reach the banks of the Rhine River.

In late 1917, the U.S. War Department, now the Department of Defense, established two all-black divisions — the 93rd Infantry Division and the 92nd Infantry Division. The 93rd fought under France’s 4th Army. The 92nd Division did not do well in the Battle of Argonne Forest, which was used by racist military commanders for the next 30 years to talk about the inadequacy of African-American soldiers.

The 92nd was given a tougher assignment by the French to harass the enemy with frequent patrol. The 92nd suffered more than 462 casualties.

On December 13, 1918, one month after Armistice Day, the French government awarded the Croix de Guerre, the country’s medal of valor, to 170 individual members of the 369th, and a unit citation was awarded to the entire regiment.

Two members of the 369th were awarded the Medal of Honor and Distinguished Service Cross.

The heroism and courage of Black soldiers frightened whites in the United States, who feared the soldiers would return home demanding their rights.

Black soldiers fought a two-front war. One against the Germans and the other against bigoted white Americans.

General John Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force along the Western Front, sent a secret communique to the French command, warning them not talk, eat with or meet with Black soldiers. He also questioned Black soldiers’ courage.

After the war, a parade was held along New York City’s Fifth Avenue to honor the Harlem Hell Fighters but most, if not all, the Black soldiers faced a great difficulty when they arrived in the United States.

In Washington, D.C., Elaine, Arkansas, Longview, Texas, Knoxville, Tennessee, Omaha, Nebraska, Chicago and 23 other cities, there were race riots, later called the Red Summer because of all the blood that was shed in the streets. In Chicago, 23 Blacks were murdered and 1,000 Black families were left homeless during 13 days of escalating violence. In Elaine, Arkansas, 100 to 240 Blacks were lynched by white mobs.

The riots were caused by several factors. Whites felt affronted by seeing Black men wearing U.S. Army uniforms. They also were upset about other issues, including labor unrest and the rise of bolshevism, sparked by the 1917 Russian Revolution.

During the Red Summer, 11 Black soldiers, some wearing their uniforms, were lynched.

This article originally published in the November 19, 2018 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.