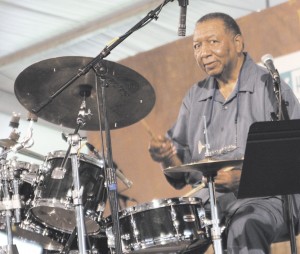

Drummer, Bob French dies

19th November 2012 · 0 Comments

By Geraldine Wyckoff

Contributing Writer

First and foremost, Bob French loved New Orleans music and deeply understood the importance of its continuance from generation to generation. Coming from a musical family, it’s how he was brought up. The drummer led the Original Tuxedo Jazz Band a position he took over in 1977 following the death of his father, its leader, banjoist/guitarist Albert “Papa” French. His shows on WWOZ-FM offered him another arena from which to trumpet the merits of New Orleans music. Bob French died on Monday, November 12, 2012, at the age of 74.

Always highly regarded by traditional jazz fans for his talents as a drummer, French enjoyed a growing reputation among the general population when he began his notorious Monday night gigs at Donna’s Bar & Grill on North Rampart Street and when he hit the ‘OZ airwaves. With French you got a lot more than just music. You got the world according to the very funny, sometimes brutal, often controversial, always-opinionated Bob French

“He was hilarious,” says saxophonist Branford Marsalis, who had known French since childhood and produced, played on and released the drummer’s final recording, 2007’s “Marsalis Music Honors Bob French,” on his Marsalis Music label. “I’d put him online just to hear him go off on people which he did with regularity. His shit was just pure unadulterated funk.”

From behind the drums, French would hold court at Donna’s as if it was his own living room. Between tunes, he might turn on the charm, display his wit, or throw in a few jokes or a couple of stinging barbs. His brash tirades often stood in contrast to his laid-back approach to his instrument.

In a world where flash increasingly has become more important than the music, Marsalis says that French stood apart. “He’s not going to go for all those frills and that cute shit and harmonic substitutions – he’ll just play the tune. Bob wasn’t for all those gimmicks. You don’t play any more than the music requires to get the job done.”

“Playing with Bob French, you know exactly what you’re going to get,” says trumpeter/vocalist Leon “Kid Chocolate” Brown, who, as a young musician, benefited from the exposure he received when he began playing with French in the late 1990s. (Of note, Brown chose to use the present tense when speaking of the late drummer.) “He’s very consistent and his sound is very unique. For example, when Bob French plays a press roll on the snare drum, you’re not going to hear a press roll like that anywhere. I heard somebody say it sounded like somebody zipping up a zipper. He had his thing. He had it figured out.”

Brown acknowledges that French had a reputation for being grumpy and even mean. He explains that in his view, the drummer was offering the young people in his band a lesson in dealing with people in the business.

“He made sure that we never saw him kissing ass or getting screwed in front of us,” Brown clarifies. French’s point, says Brown, was that just because he and his generation had to go through back doors and Uncle Tom just to play the music they loved, that the young musicians of today don’t have to. “He let us know, if you take shit people are going to give you shit.”

The drummer began his long musical career playing in rhythm and blues bands and hit the road with James “Sugarboy” Crawford right out of high school. He teamed up with vocalist Art and saxophonist Charles Neville and pianist James Booker in a group called The Turquoise and was active at Cosimo Matassa’s J&M Studio during the R&B heydays including sessions with pianist/vocalist Fats Domino, producer/trumpeter Dave Bartholomew and guitarist Earl King. In the late 1960s, he was at the drums with his brother, bassist/vocalist George French’s group, the Storyville Jazz Band at Bourbon Street’s Crazy Shirley’s club. The ensemble also included pianist Ellis Marsalis, trumpeter Teddy Riley, trombonist Freddie Lonzo and reedman Ralph Johnson. Branford first met French there when the saxophonist would go to the club to hear his father play. Later, when Branford had gigs of his own with the R&B group the Creators, he’d hang at Crazy Shirley’s after his jobs.

“Bob was kind of like part of the fabric of our growing up,” says Branford of both he and pianist Harry Connick Jr. who also appears on the Marsalis Music Honors Bob French album. French, Marsalis and Connick might seem a somewhat unlikely trio of friends but they share a lot of history.

“We’re all cut from the same cloth,” Marsalis explains. “We all speak the same language. It involves a whole lot of humor, a whole of shit-talking and a whole lot of passion about music. Bob was New Orleans through and through. He was brash and opinionated and shit, I’m brash and opinionated. But that’s the language that we speak at the end of the day.”

French didn’t begin playing traditional jazz until he filled in for drummer Paul Barbarin one night at Dixieland Hall. “I discovered how much I didn’t know about the music,” he once said. “I gained all the respect in the world for it.”

As a bandleader, trumpeter Brown describes French as leading a tight ship. “It was almost military the way he ran his band. I called it Bob’s boot camp. After you went through that boot camp, you could run a band.”

While Brown appreciates and benefited from such lessons and the exposure he received playing with French, he says that it was all a part of the drummer’s goal to hand down the music to up-coming musicians.

“I wouldn’t say he did it so much for us but for the higher purpose of continuance,” Brown offers. “It wasn’t necessarily for any individual to be limelighted or catapulted into stardom as much as it was for the tradition that was passed on to him to be passed on to the next generation.”

Many disparate adjectives from charming and gregarious to cantankerous and worse have been used to describe Bob French. At one point or another the descriptions were undoubtedly true. At all times, however, he was a talented drummer who was devoted to the music. Bob French was a New Orleans icon whose music and biting wit will be remembered and missed.

This article originally published in the November 19, 2012 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.