A closer look at law enforcement inside our nation’s public schools

11th April 2016 · 0 Comments

By James A. Gilmore

Contributing Writer

(Special from TriceEdney-Wire.com) – Last month, the Civil Rights Coalition on Police Reform (CRCPR) co-convened by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, and the Civil Rights Roundtable on Disability met with leaders in the administration to discuss best practices and sound policies for maintaining school safety. Among the reforms discussed was greater accountability for school resource officers (SROs) who serve inside public schools. Use of force by SROs has a negative impact on students, particularly along lines of race and disability status.

Notably, students of color figure prominently into the many stories of police brutality and excessive use of force that continue to make headlines. In October of 2015, a video emerged of a student being violently removed from her chair by a school resource officer (SRO) at Spring Valley High in South Carolina. In the same month, the Department of Justice filed a statement of interest in a Kentucky school case where eight- and nine-year-old boys were handcuffed behind their backs, above their elbows and at their biceps for behavior that stemmed from Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). And in March of 2016, The Washington Post reported that the Baltimore school system’s police chief and two officers have been placed on administrative leave after a video surfaced of officers violently beating a young man.

The President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing’s final report highlighted the need for law enforcement agencies and school districts to establish memorandums of understanding (MOUs) to limit police involvement in student discipline. MOUs would delineate specific roles and responsibilities for SROs and limit their participation in non-criminal school discipline matters, and could require specific training and supervision. The Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) office of the Department of Justice released a fact sheet outlining how to develop a successful MOU.

In addition to defining roles, accountability measures are necessary for the federal government to ensure recipients of federal grants do not engage in discriminatory behavior. Last year, the COPS office awarded $113 million in hiring grants giving special consideration to departments in need of SROs. The Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1698 and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 strictly forbid discrimination on the basis of race, color, sex or national origin by law enforcement agencies receiving federal funds.

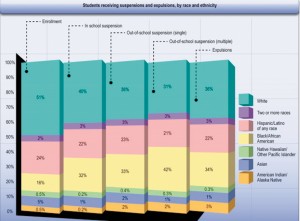

Lastly, schools should rethink their approach to discipline in light of the documented racial disparities in suspensions and expulsions. The Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights reported that while Black children represent 18 percent of preschool enrollment, they represent 48 percent of children who receive more than one out-of-school suspension and “black children are suspended and expelled at a rate three times greater than white students.” For schools that rely on SROs, a disproportionate rate of discipline for students of color and students with disabilities may mean a disproportionate rate of contact with officers.

While many people believe SROs should be replaced with social workers or trained specialists with a background in child development or mental health, others believe SROs are necessary to prevent incidents like the tragedy at Sandy Hook Elementary. Even so, advocates agree that the time for school discipline reform is now. In his last term, President Obama is focused on improving our criminal justice system—one that has traditionally worked against people of color. One way to improve the criminal justice system and dismantle the school to prison pipeline is by limiting the use of police in school discipline, curing racial disparities in school suspensions and expulsions, and creating accountability for law enforcement in schools.

This article originally published in the April 11, 2016 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.