Deconstructing Reconstruction

19th August 2013 · 0 Comments

By Nicholas Lemann

Contributing Writer

Editor’s Note: This is the fifth in a series Race in America — Past and Present America’s Twentieth-Century Slavery.

(TriceEdneyWire.com) — Children in elementary school often come home with the idea that the purpose of the Civil War was to end slavery but if that were true, then why did it take Abraham Lincoln so long to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, and why was it less than universally popular in the Union states?

If you see the movie Lincoln, you get a much fuller picture of the contingency of emancipation, and of the difficulty of passing the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery completely but why didn’t Lincoln and the Congress think to address at the same time the obvious question of what status the freed slaves would have after that?

The tumultuous decade that followed the Civil War failed to enshrine Black voting and civil rights, and instead

paved the way for more than a century of entrenched racial injustice.

After Lincoln’s assassination, Congress and the state governments settled that matter by passing the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, which gave the former slaves full civil rights and voting rights-but why was it necessary for exactly the same rights to be reenacted, after enormous struggle, nearly a century later, during the civil rights era?

The answers to all these questions are essentially the same: For most of American history, White America has been highly ambivalent, or worse, about the idea of full legal equality for Black Americans. Emancipation itself was a forced move, an obvious consequence of the war only in retrospect; it happened because in war zones in the Confederate states, slaves left their plantation homes and appeared at Union army encampments (they were known at the time as “contraband”), and somebody had to decide what to do about them; sending them back to their owners would be both morally suspect and a form of material aid to the enemy.

There has always been a debate about what kind of Reconstruction regime Lincoln would have instituted after the war, had he lived; his racial impulses were generous, but he was not an abolitionist until he actually abolished slavery. Reconstruction-the tumultuous decade or so that followed the Civil War-was an enormous shaping force in American history, and not just in the area of race relations. It’s worth recounting in basic outline, because it’s a far less familiar story than that of the Civil War itself, but far more relevant today.

The word “Reconstruction” is somewhat misleading in the American case, because it implies that the main challenge was managing the tension between punishing the South for seceding and getting it back on its feet economically and politically. In this instance the more pressing question was what the lives of the millions of freed slaves in the South would be like.

Would they be able to vote? To hold office? To own property? To sue white people? Would government undertake an active, expensive effort to educate them and put them on the way to economic self-sufficiency? Merely to say that former slaves were now free turned out to resolve remarkably little.

In the period just after the Civil War, Lincoln’s vice president and successor, Andrew Johnson, was impeached for moving too slowly on these matters, and for being too lenient with the South. Then the fiercely antislavery “radical Republicans” took power, rammed through the Fourteenth (civil rights) and Fifteenth (voting rights) Amendments, maintained the presence of federal troops in the South to enforce those laws, and ran a proto-War on Poverty through a new federal agency called the Freedmen’s Bureau, which was meant to help the freed slaves. Just as the Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment were enormously controversial in the North as well as the South, so too — only more so — were these “radical Reconstruction” measures.

The freed slaves never got “forty acres and a mule,” a land-reform idea that has resonated through the years but wasn’t enacted (see “Rumors of the Land” but they did get the basics of citizenship-most importantly, the right to vote. One of the most amazing achievements in the history of Black America was the creation, in just a few years, of an elaborate political machinery-Republican, of course-that produced far higher (in fact, pretty close to 100 percent) voter turnout among freed slaves in the South than the United States as a whole has now. One result of this was that the South elected dozens of Black officials to national office, and another was that state and local governments delivered, at least to some extent, what the freed slaves wanted, notably education at all levels.

None of this was especially popular in the North and it was wildly unpopular in the white South. Most of the rest of America chose to understand Black political empowerment in the South in terms that are still familiar in conservative discourse today: excessive taxation, corruption, and a power imbalance between federal and state government.

These arguments were more presentable than simply saying that Black people shouldn’t be allowed to vote, and they built sympathy for the white South among high-minded reformists in the North who were horrified by the big-city political machines that immigrants had created in their own backyard. Good-government reformers hated the idea of uneducated people taking over the democratic machinery and using it to distribute power and patronage, rather than in more high-minded ways. Liberal northeastern publications like The Nation, the Atlantic Monthly, and Harper’s Weekly were reliably hostile to Reconstruction, and their readers feasted on a steady diet of horror stories about swaggering corrupt black legislators, out-of-control black-on-white violence, and the bankruptcies of state and local government.

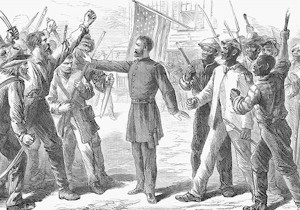

The Ku Klux Klan, which began in the immediate aftermath of the war and was suppressed by federal troops, soon morphed into an archipelago of secret organizations all over the South that were more explicitly devoted to political terror. These organizations-with names like White Line, Red Shirts, and White League-had shadowy ties to the more respectable Democratic Party. Their essential technique was to detect an incipient “Negro riot” and then take arms to repel it. There never actually were any Negro riots; they were either pure rumor and fantasy that grew from a rich soil of white fear of Black violence (usually entailing the incipient despoliation of white womanhood) or another name for Republican Party political activity, at a time when politics was conducted out of doors and with high-spirited mass participation.

The white militia always won the battle, if it was a battle, and nearly all the violence associated with these incidents was suffered by Black people. In the aggregate, many more Black Americans died from white terrorist activities during Reconstruction than from many decades of lynchings. Their effect was to nullify, through violence, the Fifteenth Amendment, by turning Black political activity and voting into something that required taking one’s life into one’s hands.

All of this was known at the time (the movie Birth of a Nation can be seen as an extended brag about the effects of these techniques during Reconstruction), and there was no mystery about what the remedy to Southern political terrorism was: federal troops. Just as in every “Negro riot” the white militia won, in every encounter between the U.S. Army and a white militia, the Army won.

The Army was in the South to enforce the Fourteenth and Fifteen Amendments, and it became increasingly clear that without its presence, the white South would regionally nullify those amendments through terrorism. But the use of federal troops to confront the white militias was deeply unpopular, including in the North.

Remember that in the 1870s, despite the Civil War, few Americans thought of their national government as properly occupying an ongoing active presence in their lives. The country had never been entirely for full rights for African Americans in the first place, and it wanted to put the Civil War and its legacy behind it. In January 1875, troops under the command of General Philip Sheridan, the great Union cavalryman, marched onto the floor of the Louisiana legislature to ensure that representatives elected by Black voters would be seated. This incident was denounced by virtually every respectable liberal voice in the North; at a public protest meeting in Faneuil Hall in Boston, most of the leading white former abolitionists demonstrated that they had turned against Reconstruction. It’s a clear example of the idea that the past is another country-it is hard for us to imagine today how abolitionists could support emancipation but not full Black citizenship, but many of them did.

President Ulysses S. Grant, perhaps out of conviction and perhaps out of political calculation (Black Southern voters were a big part of the Republican electoral base), placed himself close to the pro-Reconstruction edge of white opinion. Every member of his Cabinet was more hostile to Reconstruction than he was. But he did not feel confident that he could empower federal troops again and again to enforce Black voting rights until the South finally accepted those rights. The crucial moment came in the fall of 1875 (election dates were less standardized then than they are now), when Mississippi and Ohio held state elections.

White terrorists in Mississippi made it clear, by arming themselves and disrupting Republican political activity, that they intended to suppress the Black vote to the point that the Democrats would win. A group of Ohio politicians visited Grant and told him that if he had federal troops enforce the Fifteenth Amendment in Mississippi, it would be so unpopular in Ohio that the Democrats would win there. Grant tried to compromise by sending a negotiator to Mississippi to broker a peace treaty between the Republicans and the white Line organization, but the Democrats immediately violated the treaty, there was a wave of electoral violence in November, and the Democrats swept back to power (while the Republicans held Ohio).

The next year, militia organizations across the South copied “the Mississippi plan” for Black vote suppression, and this was one reason the 1876 presidential election ended in a tie-which was resolved by the Republicans promising to withdraw federal troops from the former Confederacy, in return for the presidency. From that point on, enforcement of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments in the South grew increasingly lax.

Whites with guns “called upon” politically active Republicans, Black and white, and urged them to move to the North or drop their political activities-and the advice was frequently taken. By the 1890s the Southern states were able legally to institute the Jim Crow system, which formally rescinded Black civil rights and voting rights, without challenge from the federal government. Through at least the first half of the twentieth century, most white Americans, North and South, understood Reconstruction to have been a miserable failure on its own terms, and even most liberals regarded Jim Crow as an impregnable fortress. In 1957, Congress passed a civil rights bill, and President Dwight Eisenhower sent federal troops to the South to ensure Black Americans’ rights (specifically, the right to attend Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas) – the first time either had happened since 1875.

Once your ear is tuned to hear them, echoes of Reconstruction are all around us today. The distinctive voting patterns of the South are a product of Reconstruction and Jim Crow, and the dramatic switch in the South’s political loyalties beginning in the 1960s is a direct result of the Democratic Party’s aligning itself with the original goals of Reconstruction. Reconstruction was the beginning point for most of our debates about the proper size and extent of the federal government; the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments were the first important measures directing the national government to do something affirmatively, rather than forbidding it to do something.

It’s no accident that African Americans are consistently the group with the most favorable view of government; essentially all of their progress toward full legal equality came as a result of government-specifically, federal government-action. Periods of greater state and local power were periods of at best no progress, and at worst more terror. And psychologically, the yawning gap that still exists between the way whites and Blacks understand Reconstruc-tion-which, unlike the Civil War and the civil rights movement, has had almost no depictions for popular audiences since the days of Gone With the Wind, but gets communicated privately inside family homes in very different ways-must partly account for what remains of the profound gaps between the races in their perception of the essential nature of the national project.

This article originally published in the August 19, 2013 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.