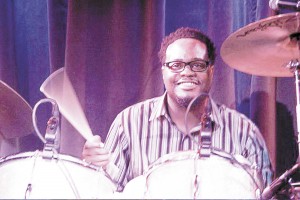

Derrick Freeman – Can’t judge a book…

8th December 2014 · 0 Comments

By Geraldine Wyckoff

Contributing Writer

The saying goes, you can’t judge a book by its cover meaning outward appearances can be misleading or misinterpreted. That goes for album covers too as is the case with drummer/vocalist Derrick Freeman’s latest, ultra-hip release DWB. Provocative to be sure, it looks mean and violent with a would-be attacker grasping a big knife for use on an unsuspecting victim. The image has caused much controversy for seeming to condone thug mentality.

Freeman, who portrays both the potential victim and the assailant in the photo, explains that the image has both history and a deeper meaning. For one, it is a depiction of a painting by New Orleans artist, the late Roy Ferdinand, known for his “urban realism” series, that hangs above the couch in the green room at the House of Blues.

“Every musician recognizes it immediately,” Freeman points out. “I always wanted to do a cover that I am in my own worst enemy type situation,” Freeman continues. “I want to be loved, and I want to get gigs but I think my mouth – the shit I say and my opinions – gets me put out of stuff like that. At times I feel the things that make me a good artist also make me not accessible. I thought it would be cool to have a New Orleans reference in the statement that I wanted to make so it’s also homage to a great artist.”

Freeman’s professional persona as an animated, fun loving, talented drummer with trumpeter Kermit Ruffins’ Barbecue Swingers and the rapping leader of his group Smokers World, could also be viewed as belying the depth of his endeavors and musical background.

A native of Houston, Texas, Freeman attended The High School for the Performing and Visual Arts where he studied classical piano and percussion.

“I was set on being a classical musician and composer,” he says, adding that his intent was to go to Julliard. “I did play drums in church and didn’t get into jazz until my senior year. New Orleans wasn’t on my radar.”

Though Freeman was accepted into a number of well-regarded schools, the highly competitive Julliard was not one of them. He had pretty much decided to attend a university in Texas but a talk with Ellis Marsalis changed all that. Freeman remembers Marsalis saying, “Naw, you should come to UNO,” after the two met following a show in Houston where Freeman and his his high school band opened for the pianist and head of the Jazz Studies department at the University of New Orleans.

“I auditioned, they gave me a scholarship and I came a month later,” Freeman says of the rapid transition. He was just 18 years old.

Having met drummer Shannon Powell, trumpeter Jeremy Davenport and bassist Neal Caine when they performed with Harry Connick Jr.’s band in Houston, Freeman quickly jumped into the New Orleans scene. He also began taking lessons with Powell.

“Walter Payton was the first guy to really give me gigs and he was the first person I left the country with,” says Freeman who remembers playing spots like the Jazz Showcase and Kemp’s with the bassist in the early 1990s.

“I was a good student for the first three semesters,” says Freeman with a laugh. “That was until (bassist/saxophonist) William Terry said, ‘You should come to Joe’s (the now-defunct Joe’s Cozy Corner).’”

The club, located in the heart of the Treme neighborhood, was where Freeman met Ruffins, trombonist Corey Henry and the great Anthony “Tuba Fats” Lacen. Or as Freeman describes it, “pretty much everybody.” Eventually, the drummer began subbing in Ruffins’ band for Jerry Anderson and Powell and went to Finland with the trumpeter with 16-year-old Irvin Mayfield at the piano.

Importantly in his development as a jazz musician the drummer “inherited” the Sunday night jam session at Café Brasil playing there with the UNO Jazz Trio. “That’s where I got most of my training – there and the old Café Istanbul (then on Frenchmen Street) and Donna’s.

Freeman found his voice as a member of Cronk, a band that favored songs from the 70s and 80s from the likes of Bobby Womack and Sly Stone. “All the stuff I grew up listening to.” It was with Cronk that Freeman first sang “If You Want Me to Stay,” that has become his signature with the Barbecue Swingers. While singing from behind the drums, he remembers realizing that the delivery would be a lot more effective if he was out front.

In 2007, Freeman jumped to center stage leading his own group. With his lively personality, showmanship, dance moves, humor and ability to connect with an audience, front and center was a natural spot to present his music his way.

“The actor in me kinda takes over with that type of stuff,” says Freeman, who humorously explains that he has done “bit parts in big movies and big parts in movies you have never seen. Honestly, I learned a lot from Kermit and I learned a lot from Keng {vocalist and falsetto master Keng Harvey, a member of Freeman’s band who’s heard on the album}. Keng and I have been close for a lot of years. I was a huge fan of Iris May Tango.”

Freeman brings all of his talents to DWB, the initials of which stand for Driving While Black that is particularly apt during a time when there’s such focus on walking while Black. He agrees that the album plays like listening to the radio. There’s a thread that exists in the music despite major stylistic transitions. It moves from rap to the suggested reggae rhythms and the hysterical lyrics of the CD’s most popular number, Freeman and Jamie Bernstein’s “Jimmy.” That tune is immediately followed by the straight-up jazz of pianist Cedar Walton’s “Black” that features such notables as trumpeter Nicholas Payton and saxophonist Derek Douget.

“Everybody listens to their iPods on random now. So if you were listening to the Derrick Freeman station, this is what it would be.”

With its slew of local musicians including horn players, strong rhythms and sense of humor, above all else, DWB sounds like New Orleans.

“My whole identity as a musician was shaped by this town,” Freeman, 40, acknowledges. “I was a kid with a lot of talent but no direction – I was a choir boy when I moved here,” he adds with a laugh.

This article originally published in the December 8, 2014 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.