First Black astronaut remains a forgotten pioneer

6th March 2017 · 0 Comments

By Erick Johnson

Contributing Writer

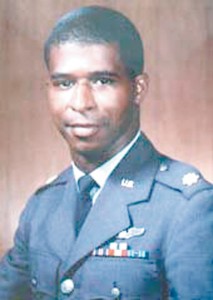

NASA barely mentions Robert H. Lawrence Jr. during anniversaries, memorials

(Special from Chicago Crusader) – Two historic events that changed America occurred 50 years ago. While many will remember the 50th anniversary of the failed Apollo 1 space flight, an equally historic event that affected Black America remains largely forgotten.

The 50th anniversary of the tragic death of America’s first Black astronaut, Major Robert H. Lawrence, will perhaps go unnoticed in 2017. Lawrence was a determined individual whose career into space never got off the ground. Like the three white astronauts who perished during a fire on the Apollo 1 flight, Lawrence’s dreams of orbiting the earth also ended in tragedy.

Ambitious and fearless, he aspired to venture to the moon at a time when people of color were not wanted in parks, restaurants, and neighborhoods here on earth.

Lawrence’s launching pad was his hometown of Chicago, where he blasted through high school and graduated at just 16 years old. Poor and Black, Lawrence faced tremendous odds against breaking into the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) lily-white stratosphere, but when he did, he became America’s first Black astronaut.

Black pride turned to sorrow after Lawrence was killed in a jet crash at Edwards Air Force Base in California. The accident happened just 11 months after an electrical fire aboard a rocket in flight killed three Apollo I astronauts on January 27, 1967. This year marks the 50th Anniversary of the deaths of four astronauts, but NASA and America have remembered the three astronauts in the Apollo 1 disaster as heroes, with special commemorations, while Lawrence remains a forgotten pioneer whose memory has been lost.

Robert Lawrence contributions to NAS reinvigorated Black America, but there won’t be any ceremonies and special events to mark the 50th Anniversary of his untimely death. Lawrence’s struggle remains the same in death as it was in life: getting recognized as an astronaut at NASA.

Despite campaigns and efforts to recognize his contributions, Lawrence’s legacy is drifting like a wayward space satellite. Once a celebrated pilot who flew over 2,500 miles, Lawrence today is rarely honored on the same level as other NASA astronauts who have gone on the ultimate mission.

Schools and scholarship funds named after Lawrence have vanished, and with Lawrence’s most avid crusaders of his legacy gone (his wife, mother and other relatives), the legacy of a man who inspired many Blacks to dream big has faded over five decades.

Before the release of the movie, “Hidden Figures,” many Blacks were unaware of the historic contributions of Black NASA mathematicians Katherine Johnson, Mary Jackson and Dorothy Vaughan. Though it was Johnson’s use of analytic geometry that helped bring John Glenn back to Earth, she was among the few Black heroes who toiled, unsung, behind the scenes at NASA, where only three percent of 19,000 employees were Black in 1961. Morehouse, Tuskegee University (then Tuskegee Institute) and other historically Black schools were cranking out physicists, scientists and mathematicians every year, but many did not apply to NASA. Some Black leaders accused NASA of not working hard enough to recruit minorities.

From its inception astronauts were considered the face of NASA. All of them were white and male. Though working for NASA behind the scenes was difficult for Blacks, becoming an astronaut was considered a seemingly impossible mission for people of color.

After Black voters propelled John F. Kennedy into the White House in 1961, his administration aimed to increase minorities at NASA, as well as to place a man on the moon. Kennedy wanted to make history by selecting the first Black astronaut.

In 1963, NASA officials chose Ed Dwight to train at the Aerospace Research Pilot School to go into space. NASA eventually did not select Dwight for its space mission. While the agency said his academic qualifications weren’t good enough, many Blacks believed the failure of his candidacy was based on racism. The Black Press, including the influential EBONY and Jet magazines, wrote aggressively about Dwight’s experience.

Dwight left the Air Force and became a sculptor. He created the statue of former Chicago Mayor Harold Washington, which stands outside the eponymous cultural center in the Windy City.

With Dwight gone, Lawrence’s NASA candidacy renewed the hopes of Black America; he was brilliant and had impressive credentials. As Dwight’s hopes of flying into space crashed, Lawrence’s career was gaining altitude.

Lawrence never made it to the stars. On December 8, 1967, he died while training another NASA astronaut to land a F-104 Starfighter Jet. The exercise was part of a six-month training program. Lawrence sat in the rear seat as trainee Major Harvey Royer landed the jet too fast, causing it to crash on the runway. The landing gear collapsed, the canopy shattered and the plane bounced and skidded on the runway for 2,000 feet. Royer was ejected but escaped, albeit with serious injuries.

Lawrence was still strapped to his ejector seat, however, his parachute failed to open. He was dragged 75 feet from the wreck. Just 32 years old, Lawrence was dead and so, too it appeared, were Black America’s dreams of a Black astronaut in space. Even so, the fact that he was training a white pilot was an extraordinary contribution during an era when segregation and racism at NASA was still prevalent. While Lawrence’s death stunned America, the loss deeply affected Black America, which was still trying to push past the disappointment of NASA not selecting Dwight as an astronaut.

Sadly, Lawrence’s grieving widow, son, and parents would suffer emotionally in the years to come. In 1991 at the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida, the Astronaut Memorial Foundation (AMF) dedicated a memorial in honor of astronauts who gave their lives for the space program. NASA didn’t consider Lawrence an astronaut, saying he had never flown 50 miles. After a public campaign led by Illinois Congressman Bobby Rush, Lawrence’s name was added to the memorial in 1997, 30 years after his death. His widow, son, mother and sister attended the dedication.

Time has shown that Lawrence is nothing more than a name to NASA. Though his name is engraved high above on the Space Mirror Memorial, NASA doesn’t hold anniversary remembrances of Lawrence the way it does for other deceased astronauts.

As the 50th anniversary of Lawrence’s death approaches, a NASA official told the “Chicago” Crusader that unlike ceremonies held in Washington and at Cape Canaveral for the three Apollo 1 astronauts, there won’t be a 50th anniversary remembrance ceremony honoring Lawrence.

Fifty years after his death, NASA still maintains that Lawrence was never an astronaut. On its website, the agency mentions the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 1 astronauts, but mentions nothing about the 50th anniversary of Lawrence’s death. Asked why NASA would add Lawrence to its astronaut memorial, yet not commemorate his other historic milestone, the NASA official referred the “Crusader” to another department, which did not respond to the reporter before press time.

It gets worse for Lawrence’s legacy. A scholarship fund set up in Lawrence’s name at Bradley University after he died, was discontinued years ago. And the Robert H. Lawrence Elementary School on the South Side closed in 2013 due to declining enrollment and low academic performance. Englewood High School, Lawrence’s alma mater closed in 2008 for similar reasons.

Some 16 years after Lawrence’s death, Guion “Guy” Bluford became the first Black astronaut to fly into space. Chicago’s Mae Jemison became the first Black woman astronaut in 1987. In 1996, Chicago’s Joan Higginbotham became the third Black woman astronaut.

Since Lawrence’s death in 1967, 13 Black astronauts have traveled into orbit, including Charles Bolden, who became the first Black administrator to head NASA under President Obama’s administration. While Bolden, Jemison and Higginbotham enjoy new careers since their historic flights to space, for Chicagoans and nationally, Lawrence remains a hidden figure.

This article originally published in the March 6, 2017 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.