Native son is finally honored as war hero

17th September 2012 · 0 Comments

By Mason Harrison

Contributing Writer

Federal lawmakers paid homage earlier this summer to a group of Black World War II veterans who, until now, had not received their due as members of America’s “Greatest Generation,” the men and women who battled fascism in Europe and the Pacific after their country’s entry into the world’s second global conflict in the 1940s. On Sept. 10, Winston Burns Sr., a New Orleans native, joined the ranks of the former Montford Point Marines receiving the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian award.

“I couldn’t go to Washington to receive the award,” Burns says, who forewent the trip to participate in the original award ceremony near the Capitol to attend a family reunion. “So, they said that they would find a way for me to receive the medal somewhere locally.” Months later, Burns was invited to participate in a ceremony honoring the Montford veterans at the Marine Corps Support Facility in Algiers.

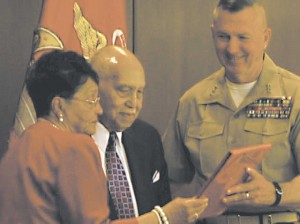

World War II and Montford veteran Winston Burns Sr. is presented his Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian award, by Lt. Gen. Steven A. Hummer, during ceremonies held last week.

“I thought there was going to be just a small group of people there,” Burns says about the ceremony, “but they brought out of all these Marines – men, women, Black and white.” Burns says he believes Marine Corps higher-ups organized the large contingent of Devil Dogs “to show these young Marines that they can do anything.” Burns thanked the present-day members of the Corps for serving in the armed forces and was treated like a rock star following his speech. “I shook so many hands that day,” he remembers. “They just kept coming up to me—especially some of the other Black men—and thanking me for what I had done and I responded by thanking them.”

Black enlistees in the segregated Marine Corps during World War II were trained at a facility in Montford Point, N.C., before seeing action abroad. “It may sound strange, but I had no idea I’d be entering a segregated Marine Corps,” Burns says. Other branches of the military were integrated at the time and Burns assumed service in the Corps would be no different. But to his surprise he and other Black fighters faced “direct and indirect segregation.” Burns remembers that there were “certain jobs that you couldn’t get” as a Black Marine in addition to being separated from white members of the Corps until the branch was integrated by a presidential order.

“But segregation is over now,” Burns says, adding, “It took them 60 years to recognize us, but it’s over.” Burns says he and his fellow Black Marines “never had time for any bitterness,” but he does have one regret. “This is nice, but it came too late for my brother Leonard.” Leonard Burns, his older brother, also enlisted in the segregated Marine Corps at Montford Point, but is now deceased. The congressional recognition of the Montford Point Marines is for all of the approximately 20,000 men who endured boot camp there.

The Montford Point Marine Association, formed in 1966, estimates there are seven living Montford alumni in Louisiana and the city’s National World War II Museum provides educational materials and programming for teachers, students and other interested parties on Black service in World War II, dubbing their efforts as the fight for “Double Victory” over fascism abroad and racism at home.

In June, Montford veteran William McDowell received the Congressional Gold Medal on behalf of all of the Montford Marines in keeping with tradition when presenting the award to a group of honorees. The Congressional Gold Medal differs from the military’s Medal of Honor because it is an award bestowed by the country’s legislative branch and not officials in the armed services and enjoys prestige on par with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

This article was originally published in the September 17, 2012 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper