Protesters march against racist statues to pressure officials to take action

7th December 2015 · 0 Comments

By C.C. Campbell-Rock

Contributing Writer

After waiting 180 days for the required protocol for the removal of at least four Confederate monuments from public spaces, to be completed, last Saturday during Bayou Classic 2015, more than 50 protesters came together to send a message to city leaders: “Take down the statues honoring white supremacists now.”

The Rally & March for the Removal of Racist Monuments was spearheaded by the “Take ‘Em Down NOLA coalition and BYP-100, New Orleans Chapter. The protesters cut across all ethnic, social, and economic lines. Young adults comprised the majority but some veteran civil rights activists participated, including Malcolm Suber, the Rev. Raymond Brown, and Leon Waters of the Louisiana Museum of African American History & Hidden History Tours. Members of the National Lawyers Guild, led by civil rights attorney Bill Quigley, attended as observers. It was a profound teaching, learning, and passing the torch moment.

The protest obviously reached the ears of city leadership. Next Thursday, December 10, the City Council will finally vote on the ordinance to remove the confederate monuments.

Protesters in favor of removal and against, launched campaigns after New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s July 9, appearance before the City Council. Landrieu argued in favor of removing larger-than-life statues of Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee and P.G.T. Beauregard, Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and the Liberty Place Monument. “Those statues were erected when supremacy was the order of the day but they should not be a part of our future. Remembrance, yes, celebration, no,” Landrieu advised. “These statues and symbols reflect the opposite of our shared values.”

Between then and now, the statues were deemed a “public nuisance” and city leaders agreed that the monuments should come down. Still, no firm date for removal has been set.

The rally took place in Jackson Square, the first stop on a tour of four monuments in the French Quarter. Interestingly, the Liberty Place Monument was the only one on the tour slated for removal by the city council’s ordinance. The other monuments visited were Andrew Jackson’s Equestrian Statue, Chief Justice E.D. White, U.S. Supreme Court, and Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, founder of New Orleans.

“As a veteran organizer and activist, I have to pass the torch, so when we’re off the scene,” the fight for social, economic, and equal justice will continue, Suber explained. “We’re trying to bring attention to the lack of follow-up from the mayor and the city council around the removal of these white supremacists’ monuments.” During the tour, Suber shared the historic misdeeds of each person immortalized in stone. “Andrew Jackson owned more than 100 slaves,” he told protesters.

Jackson, the seventh President of the United States and a native of Waxhaw, South Carolina, is best known and celebrated for defeating the British during the Battle of New Orleans. But his legacy as a planter, merchant, and slave-owner is almost never elucidated. Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage, a 1,000-acre cotton plantation, is located just outside of Nashville, Tennessee. Today it is a museum.

“In all reality, slavery was the source of Andrew Jackson’s wealth…,” according to a narrative on the Hermitage’s website. “Thus, the Jackson family’s survival was made possible by the profit garnered from the crops worked by the enslaved. At the time of his death in 1845, Jackson owned approximately 150 people.”

Jackson also created the Trail of Tears. According to a PBS biopic, “He was committed to the policy of removing Indians from desirable lands and relocating them to what became Oklahoma. By 1838, the policy of relocation had essentially cleared the natives from the southeastern lands east of the Mississippi River.

Stopping by the St. Louis Cathedral, organizers’ chanted in sync with a brass band playing for spare change, “Down with white supremacy, up with the people’s empowerment.” Organizers noted the Catholic Church’s deafening silence on slavery, to which it turned a blind eye and Jim Crow, which it honored by making Blacks in the church’s congregation sit in the back pews, until the Brown v. Board of Education decision.

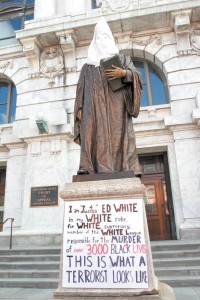

Approaching the Wildlife & Fisheries Building on Royal Street, which houses the Louisiana State Supreme Court, protesters gathered in front of the statue of Edward Douglass White, the ninth Chief Supreme Court Justice of the United States. White, a native of Thibodaux, Louisiana, was the son of Louisiana’s 10th governor, E.D. White, Sr. White Sr. served five terms in the United States House of Representatives, as an adherent of Henry Clay of Kentucky and the Whig Party.

E.D. White Jr. was a Confederate soldier. He studied law at Tulane University and was admitted to practice in 1868. White Jr. served in both the Louisiana Legislature and the U.S. Senate before becoming Associate Justice of the Louisiana State Supreme Court.

In New Orleans, he joined the Pickwick Club, a gentleman’s club formed in 1857 that became influential for its prominent members; they were of the elite and supported efforts to reinstate white supremacy, according to a Wikipedia article. He later became a member of the Crescent City White League, a statewide group that developed numerous chapters beginning in 1874. This paramilitary organization worked to disrupt Republican politics, suppress Black voting, and support white Democrats in regaining political dominance in the state.

Perhaps, the most glaring racist act White perpetrated was his support for the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, which federalized Jim Crow and ushered in nearly 50 years of segregation; White’s ‘separate but equal’ doctrine. That decision also cemented ideologies of white supremacy and white superiority and the practice of white dominance, from which this nation has never recovered. Following a brief history of White, one protester climbed upon the statue and placed a KKK hood on the man considered by some historians as “the greatest jurist of the state.”

Marchers moved on to the statue of the colonizer of Louisiana, former governor, and founder of New Orleans, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville. Bienville was a native of what is now Montreal. Fearing insurrections of Black slaves, first brought to the colony under his direction, Bienville promulgated (1724) the Code Noir. The Black Code was both oppressive and repressive; tantamount to prison for the enslaved. Its 55 articles dictated every facet of the slaves’ lives. Depicted in the statue with Bienville is a Catholic priest and a Native American. The nation figure was both intriguing and a blatant attempt to rewrite history, because Bienville allegedly “led strenuous but indecisive expeditions (1736, 1739–40) against the Natchez and the Chickasaw,” nations in an effort to rid them from the Louisiana territories, according to a brief bio on the Library of Congress site.

The march ended at the Battle of Liberty Place Monument, which sits behind the Marriott Hotel at the end of Iberville Street. Of all the monuments dedicated to the Confederacy, this one screams racism. The Battle of Liberty Place was an attempted insurrection by the Crescent City White League against the legal Reconstruction state government on September 14, 1874, in New Orleans, the-then capitol of Louisiana.

Emboldened by white sympathizers at The Daily Picayune and fellow Crescent City League member and a future U.S. Supreme Court Justice, E.D. White and City officials, the obelisk celebrating white supremacy was erected in 1891. Continuing its support for the “lost cause,” in 1932, the city added an inscription: “[Democrats] McEnery and Penny having been elected governor and lieutenant-governor by the white people, were duly installed by this overthrow of carpetbag government, ousting the usurpers, Governor Kellogg (white) and Lieutenant-Governor Antoine (colored). United States troops took over the state government and reinstated the usurpers but the national election of November 1876 recognized white supremacy in the South and gave us our state.”

As chants of “Black power” reverberated across America, the city in 1974 added a marker disavowing the white supremacist sentiment expressed during post-Reconstruction. Protesters in the early 1990s got the statue removed temporarily but were unsuccessful in keeping it from the public view. David Duke, former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, sued for its return. In July 16 of 1993, the New Orleans City Council voted 6 to 1, to declare the monument a nuisance. The monument was moved to where it stands today.

Protesters and supporters of removing the monuments have faced opposition from whites, who said the monuments are about history and heritage and should not be removed and from Blacks who have said the Black community has far greater problems to be solved and removing monuments should not even be on the Black agenda. Problems of unemployment, Black on Black crime, education, and economic parity are issues that are plaguing the Black community far more than statues.

So why are these young adults engaged in the fight to remove these monuments?

“I grew up in New York and moved to New Orleans at 12. I studied psychology and I had knowledge of how white supremacy works,” said Quess?, a certified instructional coach and founder of “Take ‘Em Down NOLA.” “I noticed the existence of a slave mentality here and it seemed to be intentionally done.”

Quess?, who earned a degree in business from FAMU, said he got involved in the Black Lives Matter movement and the BYP100 group after seeing young African Americans organizing for social justice around the Michael Brown murder by a white cop in Ferguson, MO. He organized “Take ‘Em Down NOLA,” to confront what he sees as blatant racist and white supremacy mentalities harbored by the continued existence of the confederate monuments, which in turn send a subliminal message that Black lives don’t matter. “I wanted to talk about why black lives don’t matter,” he adds. Quess?’s group joined a 13-city Confederate flag-burning campaign on May 25, 2015 and burned a Confederate flag at Lee Circle and burned another Confederate flag on July 4.

Since then, “Take ‘Em Down NOLA” has held forums, talk back events and has launched a petition drive on ColorofChange.org to get support for removing the monuments. The group is now hosting teach-ins on college campuses, high schools, and churches to let the community know about the insidious threat the monuments pose to progressive-minded agendas. People can contact the organization via info@takeemdownnola or #@takeemdownnola.

Christine Brown, a young photographer and aspiring filmmaker, documented the rally and march. The owner of C-Freedom Photography is a native New Orleanian, who grew up, ironically on near Franklin Avenue and Robert E. Lee Boulevard. She teaches photography in the public schools. Known simply as C-Freedom, the entrepreneur founded the New Orleans chapter of BYP-100. The local branch recently celebrated one year of activism. She is also raising funds for and working on a short film, The Essence of Now, about African-American women artists. “Our production team is all-female.” “We can’t allow white supremacist tools to be used to perpetrate violence,” Brown said.

It is estimated that the city spends at least $50,000 per year to maintain the monuments.

The Rev. Thomas Watson, founder and pastor of Watson Memorial Teaching Ministries, reportedly criticized the mayor for calling for the removal of the statues. Watson said reporter took his comments about the monuments not being a priority in the Black community out of context.

“What I said was that the monument piece is a smokescreen.” A reporter asked him about the mayor’s call to take down the monuments while Watson was at a press conference decrying Landrieu’s attacks on Black elected officials like Sheriff Marlin Gusman. I agree they are offensive and should come down but I disagree with the Mayor’s using it as a diversionary tactic. I do believe fighting about monuments should not be a priority,” Watson adds. “We have other priorities the Mayor should address, crime, education, and the economy.”

The biggest opponent to the removal of the statues is Save Our Circle, which is spearheaded by Tim Shea Carroll. Carroll who is white, could not be reached for comment, but the group’s purpose is to “Protect and Preserve All History,” according to its website. Save Our Circle.com is asking for volunteers and donations. It claims to have a petition of 21,000 signatures against removal of the Confederate statues.

Condemning Mayor Landrieu’s support for removal of the statue of Robert E. Lee, Carroll writes, “We believe that not only is this action by the mayor an attempt to ‘hide’ history from plain site, but a divisive move that will and has already divided the entire community. But most importantly, the mayor’s focus should be on more pressing issues affecting the city. On the same day he made his intentions clear at the New Orleans City Council meeting, the city reached its 100th murder. Shouldn’t the ‘monumental’ expenses to relocate, rename, or remove any of these monuments or street names, or any symbol deemed offensive, be spent more effectively?”

“I think many white ruling class have decided to give up on fighting against the removal of the statues that honor white supremacists. We have 52 percent unemployment among Black men in New Orleans and 50 percent of New Orleans’ Black children live in poverty. The connection is clear. These monuments reflect real white supremacy as exhibited in the condition of Black community. Whites are controlling all of the major economies of this city,” explains Suber.

“We chose the French Quarter for our March and rally because we needed the mayor’s friends there to relate our dissatisfaction to him. Out of more than 300 businesses in the French Quarter only four or five are Black-owned. There is not one Black bar owner on Bourbon Street or in the French Quarter. Look at what they did to Tracy Riley,” he continued. “That’s a prime example of white supremacy at work.”

Suber offered the case of retired Army Reserve Major Tracy Riley, who tried to open a supper club in the French Quarter. Before she even officially opened, a concerted effort was launched by an all-white coalition of state agency members, FQ residents, and business organizations that simultaneously requested that she not be granted a state liquor permit. Riley said her security guard was verbally abused by a FQ resident who said, “Get out of here, nigger. We don’t want your kind around here.”

“The symbols need to be removed,” Suber concluded.

This article originally published in the December 7, 2015 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.