Segregated cemeteries still ‘haunt’ La.

17th May 2021 · 0 Comments

By Allison Kadlubar, Bailee Hoggatt and Ezekiel Robinson

Contributing Writers

(LSU Manship School News Service) — Jessica Tilson spent many Sunday mornings in the early 1980s playing outside with her white friends under the shady oak trees in front of the fleur-de-lis stained glass windows of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Church in Maringouin. But as soon as the church bells rang, they parted.

“When it was time to go into the church, it was time to split up,” Tilson said.

The church has a main entrance with double doors, but members typically enter through separate doors on the sides of the building – to the left for Black members, to the right for white members. Once inside, Black and white members sit on opposite sides of the sanctuary to worship in front of one altar – even though Tilson said the church abandoned formal segregation in the 1980s.

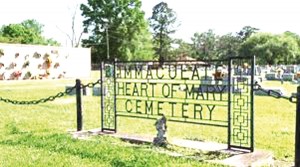

Immacualte Heart of Mary Cemetery in Maringouin, La., is just one of many cemeteries in the state that are segregated. Most provide separate spaces by race for burials, while others refuse to bury based on the decease’s race.

Photos courtesy of Allison Kadlubar/LSu Manship School News Service

Immaculate Heart of Mary Cemetery also divides graves by skin color on the left and right sides of the main pathway mirroring the church practices. The right side presents a spacious, organized pattern of granite and marble tombstones. The left side is crowded and scattered as many present-day graves are layered on top of people who, in life, were enslaved.

“By it being a small town, the Blacks are related, and the whites are related,” said Tilson, now in her 30s. “It’s only natural that all of the Blacks would be on one side, and all of the whites would be on the other side. We still practice that to this day.”

Louisiana cemeteries no longer enforce racial segregation. But customs and practices remain, ensuring that many cemeteries throughout the state are still divided by race. Directors, managers and patrons of cemeteries statewide said that while the cemeteries do not reject the burial of anyone based on race, their plots do consist primarily of one skin color.

The exact number of cemeteries still practicing similar racial customs as those enforced in the Jim-Crow era is unknown. The Louisiana Cemetery Board has certified about 2,000 cemeteries across the state.

But certification is a self-reporting process. Some cemeteries’ outdated practices, history and unidentified graves remain buried and hidden in the flat lands of Louisiana and forever marked by sunken tombstones and rusty fences.

“I think the way the culture is now – the way the world is now in certain areas – certain people do not want to touch on it,” Tilson said. “But I have no problem because it is history. It basically shows how things were at one point in time to where you can say we are still segregated, but, now, it’s family land.”

Racial segregation in cemeteries got attention recently in news reports about Oaklin Springs Cemetery in Oberlin, northeast of Lake Charles, for refusing, in January, to bury a fallen deputy of the Sheriff’s office because of his race. He was Black.

Karla Semien, the widow of that deputy, Darrell Semien, said that losing her husband was hard enough but that the cemetery’s rejection scarred her and their seven children.

“She said, ‘I can’t sell you a plot,’” Semien said. “She showed us on their contract that it was for white human beings only. It was worse than a punch in the gut, it was a stab in the heart for all of us. For the rest of our lives, it is always going to be that my husband and their dad could not be buried there because of the color of his skin.”

Unregistered Cemeteries

At the time it refused to sell a plot to the Semiens, Oaklin Springs Cemetery in Oberlin was not registered with the state, an issue that makes it harder to find out how many cemeteries remain segregated or provide proper oversight of gravesites.

Karla Semien, left, with her now deceased husband Darrell, says that a cemetery northeast of Lake Charles refused to bury her husband Darrell, a sheriff’s deputy, because he was Black.

Louisiana’s Title 8 law began requiring all cemeteries still in operation to register under the Louisiana Cemetery Board in the early 2000s. The process requires proof of property ownership, good standing in the community, financial stability, record keeping of graves and a detailed map of the grave site.

Yet some cemeteries have never registered.

Among the others are the Greenwood Cemetery in Ruston and Colvin Memorial Cemetery in Unionville (both in Lincoln Parish); Mt. Pilgrim Cemetery in Maringouin (Iberville Parish); Halsey Cemetery in West Monroe (Ouachita Parish); and Smyrna Cemetery in Downsville (Union Parish).

Lucy McCann, a Louisiana Cemetery Board director, said these cemeteries had not registered, and the board didn’t know they existed until reporters for the LSU Manship School News Service submitted public records requests. She said the board is investigating Oaklin Springs and these other cemeteries.

“The law places the burden on cemeteries to obtain a license and to self-report their existence to the board,” McCann said. “If the board is unaware of their existence, we cannot regulate them.”

But Semien thinks the board should do more to make sure families will not have to suffer like hers did.

“I think they should find them because it is the loved ones that suffer for it,” Semien said. “It is our people we are trying to lay to rest for eternity. It shouldn’t be whatever you want to do and if you want to report something.”

Neither Title 8 nor board certification requires cemeteries to be racially integrated.

“There is nothing in Title 8 that says anything related to race or any classification that would fall under the Equal Protection Act,” said Ryan Seidemann, an assistant Louisiana attorney general.

The board usually finds uncertified cemeteries scattered along bayous, rivers and gravel roads through complaints ranging from lack of maintenance to racial rejection and natural disasters.

Once a cemetery is discovered or reported, the board starts an open investigation to begin the licensure process. It opened the investigation of the Greenwood, Colvin Memorial, Halsey and Smyrna cemeteries on March 23.

Some cemeteries do not even have public contact information, a website or a recorded address. The lack of public information makes it easy for a cemetery to stay hidden.

It’s not clear how many Louisiana cemeteries remain uncertified. A study published in 1987 listed over 200 cemeteries throughout Louisiana. The study was “The Cemetery as a Cultural Manifestation: Louisiana Necrogeography.”

Few Cemeteries Respond

For this news report, journalists researched 169 cemeteries in the 1987 study. Of those, they dug up contact information for 81 cemeteries (47 percent). Six answered and agreed to be interviewed (three percent), three said they would call back but did not, 72 did not answer or have working phone numbers (42 percent), and 104 did not have any public contact information (61 percent).

Of those listed on the Louisiana Cemetery Board database, contact information may not even be a direct link to the cemetery. The information shows wrong numbers, dead phone lines and city halls as phone numbers for numerous cemeteries.

Journalists contacted district police jurors, state legislators, district attorneys, board directors and Facebook pages for contacts. For the few who responded, their information led to residents who knew little, to funeral homes or to dead ends at findagrave.com.

The lack of public information displayed by cemeteries may stem from naivety.

“Most of the smaller cemeteries that are not reporting to the Louisiana Cemetery Board don’t know that there is a mandate for them to do that, and that is not because of not trying to get the word out through existing funeral homes and cemeteries,” Seidemann said. “But it is a self-reporting process.”

But some cemeteries may be hiding to avoid regulation and criticism from the board.

“When I have been trying to get our paperwork in order to get our certificate, the lady at the cemetery board told me that there are numerous cemeteries that have not complied even though the cemetery board has been in effect since the ’70s,” said Beth Green, secretary-treasurer for the Rocky Branch Cemetery in Union Parish.

The board has authority to levy fines and has done so whenever a cemetery refuses to comply with the board’s guidelines and regulations. But Seidemann said it does not immediately issue fines and penalties if it stumbles on an uncertified cemetery.

“We don’t believe it is in the best interest of the public or consumer to ding these folks with fines,” Seidemann said. “It’s a million times more important to get them into the process and keep records.”

The secretary for the Greenwood Cemetery did not respond to a reporter’s inquiries about why it had not registered under the board. The manager of Colvin Memorial Cemetery did not know any historical information, and reporters could not find any contact information for Smyrna cemetery. Hasley Cemetery’s public phone number connected to West Monroe’s City Hall, and the secretary did not get back to the reporters regarding contacts for the cemetery.

Oaklin Springs Cemetery in Oberlin began the registration process after news reports in January showed that it had denied the Black sheriff’s deputy’s request to be buried, citing his skin color.

“I can tell you that the board has opened a formal investigation into that cemetery, so there isn’t an awful lot of detail I can go into about the investigation,” Seidemann said.

Semien, the deputy’s widow, said Creig Vizena, the president of the Oaklin Springs Cemetery Association, contacted her in March.

“He said they were going to Baton Rouge to do some kind of law for this not to happen, and they wanted to know if they could name it after Darrell,” Semien said. “They said it would be done April 12…but we never heard anything else.”

Vizena said in an interview that he pursued the possibility of a state law until State Rep. Dewith Carrier, R-Oakdale, told him a superseding federal law already barred cemeteries from refusing to sell burial plots to people of color.

He said the cemetery board has changed its contract to prevent a recurrence, and Oaklin Springs has taken steps to register with the Louisiana Cemetery Board.

He also said the cemetery employee who communicated with the Semien family knew about the contract language but was unaware of the federal law. He said that employee, who is in her 80s, no longer interacts with people seeking plots.

“Who am I to tell a mother or father that their child cannot be buried next to them?” Vizena said. “That is ludicrous.”

‘Only Black People’

A Maringouin resident, Loretta Toussant, said her fraternal relatives are buried at Mt. Pilgrim Cemetery in Maringouin, another unregistered cemetery not found in the board’s database.

“It was originally a plantation cemetery, and a lot of my family members worked on the plantation where the cemetery now sits,” Toussant said.

Workers for the plantation and their families are buried there. But all of the deceased in Mt. Pilgrim are one skin color.

“To my knowledge, there are only Black people buried there,” Toussant said.

Findagrave.com gives GPS coordinates for the cemetery but no other information.

The difference between Oaklin Springs Cemetery and Mt. Pilgrim Cemetery is that there are no “Black-only” bylaws in the latter. It developed that way through custom and familial relations, Toussant said.

Orange Grove and Graceland Cemetery in Lake Charles also is not known to have buried any Black people there, said Charles Viccellio, a retired president of the Lake Charles Cemetery Association. Again, the owners did not write white-only bylaws in the deeds, but, somehow, the cemetery hasn’t buried any people of color.

“Most burials are a matter of family tradition and did they already have someone buried in the cemetery,” Viccellio said. “Is that close to where they want to be buried, or do they like that place in particular?”

Saint Peter Cemetery is a small, crowded cemetery encapsulated by trees on the side of a black-top road in Maringouin.

Michael Pryer, treasurer and head of Saint Peter Church and Cemetery, said only Black people lie in the above-ground crypts that line the grassy area. But, he said, no Blacks-only policy was intended or enforced.

“In all of the years that I have been there for over 20 years, I don’t remember if we have ever buried someone who is not African American,” Pryer said. “I know that we don’t turn down people because of their race. We don’t turn people down.”

Pryer said his priorities extend beyond racial discrimination.

“What is important is the truth in one’s life,” Pryer said. “That is the important thing for me. What is important is that people feel welcome in the cemetery.”

Five miles from Saint Peter Cemetery lies the pathway to the segregated graves in Immaculate Heart of Mary Cemetery where Tilson played as a child.

She said today’s church members respect the deceased and their loved ones no matter their skin color.

“If a Black person died in Maringouin, the white people still showed their respects,” Tilson said. “If a white person died in Maringouin, the Black people would still show their respects.”

But Tilson believes the dated practices and customs of the cemetery will remain. After all, she hopes one day to join her deceased son, sister and parents.

“When I pass away,” she said, “I’m going to go to the Black side.”

Reporters Jordanne Davis and Ava Palermo contributed to this report.

This article originally published in the May 17, 2021 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.