The Olympics in retrospect N.O.’s own Audrey Patterson Tyler set the London Olympics on fire

23rd July 2012 · 0 Comments

By Ro Brown

Contributing Writer

Fanny Blankers-Koen was fast! So fast, that the sprinter from the Netherlands was the star of the 1948 Summer Olympic Games — the last time London hosted the world’s biggest athletic gathering 64 years ago.

Blankers-Koen won four gold medals over 100 meters, 200 meters, the 4 x 100 meter relay, and in the 80 meter hurdles. She was not called “The Flying Dutchwoman,” instead, she was dubbed “The Flying Housewife” — befitting a three-year old, mother of two, who should have been past her athletic prime.

Fanny Blankers-Koen was a first-place finisher, but the third-place finisher in race was a pioneer. Audrey “Mickey” Patterson Tyler, a 21-year-old African-American sprinter from New Orleans, won the bronze medal, making her the first African-American female to win an Olympic medal.

From Gert Town to Buckingham Palace in 25.2 seconds

Audrey Patterson’s Olympic torch was illuminated in 1944 while a student at Gilbert Academy. The ultimate Olympian, Jesse Owens, visited the St. Charles Avenue campus. She remembered the track and field legend saying, “There is a boy or a girl in this audience who will go to the Olympics.” Young Audrey felt Jesse Owens was speaking directly to her. She would work toward that dream until it was realized.

In 1947 the slender speedster went to Wiley College in Marshall, Texas. She was victorious at the highly-competitive and prestigious Tuskegee Relays in the 100- and 220-yard dashes. An undefeated season was capped off by winning the AAU National Indoor Title in the 220-yard event.

The year 1948 saw a change of scenery for Patterson when she transferred to Tennessee State in Nashville. Her dominance continued with the American record of 26.4 at 220 yards and another undefeated season.

As the Olympic trials approached, Audrey Patterson was now the most consistent winner in women’s track and field. Her performances were comparable to Wilma Rudolph in 1960 or Florence Griffith-Joyner in 1988.

According to the Associated Negro Press during its coverage of the trials in Providence, Rhode Island, she drew cheers and applause each time she passed the grandstand.

Her spot on the Olympic team was secured with an expected victory at 200 meters. She also qualified in the 100, falling short in a photo-finish to Mabel Walker. It would be the first defeat for “Mickey” Patterson since entering high school.

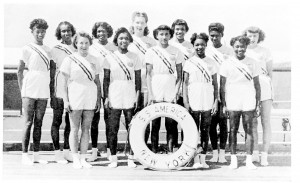

It was a historic aggregation of female athletes boarding the S.S. America in New York City, bound for London. With the addition of three new sports, the high jump, long jump and 200 meters, the number of track and field events for women reached nine. But it was the racial composition of the group making headlines. Twelve female athletes represented the United States at the first Summer Olympic Games in 12 years. The team had an unusually dark hue for the times. Nine of the 12 women were African-Americans. Patterson and Alice Coachman, the first African American to win an Olympic gold, were the only medalists for the U.S.

August 6, 1948 was a rainy day in London. The Wembly Stadium track was sloppy. From her position in lane seven, Patterson was unable to keep an eye on Fanny Blankers-Koen in lane two. It mattered little. “The Flying Housewife” won going away…unchallenged.

The race for the bronze medal, however, between Patterson and Shirley Strickland of Australia was considerably more entertaining. Both were clocked in 25.2 seconds. It would take nearly an hour before officials ruled Audrey “Mickey” Patterson the third-place finisher. However, she was a first-place finisher in Olympic history.

At 4 a m. the morning of August 28, 1948, a small crowd at Moisant International Airport welcomed the Olympic medalist home. Her neighbors in the 1300 Block of South Genois Street in Gert Town honored her with a block party. But some locals gave scant notice that a local girl achieved international acclaim.

The Times-Picayune failed to acknowledge that Patterson was a New Orleanian. Louisiana Weekly sports columnist Charles de Lay took the Picayune and sports editor Bill McG Keefe to task for the obvious snub in an August 7 column:

Too bad Mr. Keefe doesn’t seek his information. The Associated Press sends this information almost to his desk. He has only to find the desire to use the information.

Two afternoon newspapers, The States and The Item did make the New Orleans connection after Patterson’s success in London.

A testimonial was held in honor of Audrey Patterson on Sunday, September 5, at Booker T. Washington High School Auditorium. New Orleans Mayor Chep Morrison did not attend, opting to send a signed certificate of merit to Miss Patterson.

Giving proof that 1948 was no fluke, Audrey Patterson had perhaps a better year on the track in 1949. The Amateur Athletic Union named her Woman Athlete of the Year.

Modern-day athletes the caliber of Audrey Patterson can have lucrative careers. Endorsements and appearance fees at track meets in the United States and abroad have filled the pockets of a number of world-class sprinters. The mere thought of track and field athletes making money was taboo in 1948.

“The Gert Town Girl” went into education, teaching in St. James Parish and eventually moving to California with husband Ronald Tyler in 1964.

The mother of four children, she continued teaching in the San Diego area until 1980. In 1965 she formed “Mickey’s Missiles,” a youth track club for boys and girls. Dennis Mitchell, a gold medalist in Barcelona in 1992, earned his spot on the team that year with a win in the 100 meters. The speedster was a product of “Mickey’s Missiles.” Ironically the trials were held in Mickey’s hometown of New Orleans.

Audrey Patterson Tyler was a civic treasure in Southern California. Governor of the National Association of Negro Business and Professional Women, Press Club of San Diego Woman of the Year, 1st Vice-President of the Amateur Athletic Union and founder of the Martin Luther King Freedom Run.

Through “Mickey’s Missles” Track Club, Audrey “Mickey” Patterson Tyler effected the lives of more than 5,000 children. Using the sport she loved, she set out to make the world a better place. Her own words from the testimonial upon her return from the London Olympics served as a blueprint for how she lived her life:

“My greatest desire was to bring glory to my country and my community.”

Recognition at home finally came in 1978 when she was inducted into the Allstate Sugar Bowl Greater New Orleans Sports Hall of Fame in 1978 and the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame in Natchitoches in 2000.

Audrey “Mickey” Patterson Tyler died on August 23, 1996 in National City, California. She was 69.

This article originally published in the July 23, 2012 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.