Who held the first Memorial Day celebration?

8th June 2015 · 0 Comments

By Michael W. Twitty

Contributing Writer

History books credit a Union officer with the idea of a holiday to remember the war dead. But the first people to honor those who died had far less power.

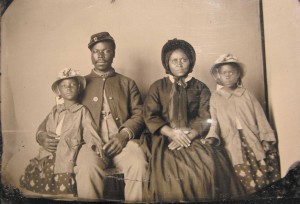

(Special from The Guardian) – African Americans have fought and died for America from its earliest days, from frontier skirmishes to the French and Indian Wars to the fall of Crispus Attucks at the Boston Massacre, immortalized as “the first to die for American freedom”. And though most official histories of Memorial Day credit with its founding a white former Union Army major general, whose 1868 call for a Decoration Day was reputedly inspired by local celebrations begun as early as 1866, the first people who used ritual to honor this country’s war dead were the formerly enslaved Black community of Charleston, South Carolina in May 1865 – with a tribute to the fallen dead and to the gift of freedom.

The city of Charleston was, like many places in the South, physically devastated by the conflict between the Union and the Confederacy, which began in its harbor with the attack upon Fort Sumter in 1861. But Charleston was more than just the place where the war of brother against brother began: it was also the entry point for a quarter of all enslaved Africans in the colonial period, accounting for more than any other port. As the international slave trade faced its inevitable abolition, traders delivered more than 90,000 humans into enslavement through the port between 1803 and the (official) end of the American slave trade in 1808. Charleston was a center for the trading of enslaved people across the Deep South and the exit point for the valuable crops of rice, indigo, and Sea Island cotton produced completely by enslaved labor – crops which made millions for the South’s wealthiest and most concentrated planter elite.

The enslaved Africans who formed the majority of the local population were some of the most un-assimilated Blacks in North America at that time. They were the Gullah people, descendants of those sold into slavery from the rice-growing regions of West Africa and the Kongo-Angola region of Central Africa. The plantations of the low country and the seedy streets of antebellum Charleston were horrific places for the Gullah people: malaria, yellow fever, cholera, malnutrition, physical violence, sexual exploitation and the constant threat of separation from the family abounded in the lives of the enslaved. Tropical diseases forced plantations into isolation and the Gullah developed their own language, a unique syncretic religion blending African and Christian elements, a food culture that birthed low country foodways as we know them, and they preserved names, stories, traditions and customs from across the African continent. One of the most important rituals that they preserved and passed on was the honoring of the ancestral dead and giving proper due to those transitioning out of this world.

When the Civil War came, the response of the Gullah people was to use their knowledge to further the cause of freedom: from the heroic acts of Robert Smalls to the enthusiasm of the Port Royal Experiment to the call for 40 Acres and a Mule, it was these uniquely cultured and empowered people who perhaps most enthusiastically embraced both resistance to the planter regime while yearning for the American dream. And, on 1 May 1865, they performed an act of gratitude to the country that had first enslaved and finally freed them, firmly based both in their African and American heritage that became part of what we now celebrate as Memorial Day.

As the war ended, behind the Italianate grandstand at Charleston’s Washington Race course – which, in the pre-war years had been the playground of the rice and cotton planter elite – there was a mass grave holding over 200 Union soldiers, because the track served an outdoor prison during the last year of the war and many prisoners died of disease and exposure. At the war’s end, after the city was surrendered to African American troops and largely abandoned by whites, the Gullah people were ready to begin facing a new reality of emancipation – but first they chose to pay homage to those who had died.

In the West African tradition from which Charleston’s Gullah people came, honorable warriors deserved sacred burial, and the dead were seen as part of a cycle of souls entering and leaving the world. To disrespect those dead was to ensure a negative energy in the future, so 28 Gullah men dug up the 200 men in that mass grave behind the grandstand and gave them proper burial – horrific work under the best of circumstances.

On 1 May, “in cooperation with white missionaries and teachers”, 3,000 Black children bearing roses led women bearing wreaths and men, marching together in a circle to honor the newly-buried war dead. Black troops were present at the commemoration — including some of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry (who were later memorialized in the movie Glory). That the Gullah people performed a march and parade in a circle was no accident: movement in a circle — the Ring Shout — was the most sacred rite brought by the enslaved to North America. In a mixture of African and American custom, the Gullah put to rest the Union soldiers, who in part, lost their lives to ensure the freedom of those who later marched for them. Black people and white marched together, and the site was dedicated as a memorial burial ground. As the children sang “The Star Spangled Banner,” the men and women wept and prayed as they expressed gratitude that the long nightmare of slavery was over.

Three years later, just days before Major General John A Logan declared that 30 May 1868 should be a “Decoration Day” to commemorate the war dead, many of the people who participated in the 1865 ceremony returned to decorate the graves of those that they’d interred. America takes time each year to celebrate the sacrifices of our war dead; this year, we should take a moment to also honor those who, despite facing hardships of their own, chose to commemorate the lives that had been lost partly in the service of securing their freedom from enslavement.

This article originally published in the June 8, 2015 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper.