Wilmington 10 prosecutor sought ‘KKK’ jury

17th September 2012 · 0 Comments

By Cash Michaels

Contributing Writer

WILMINGTON, N.C. (Special to the NNPA from the Wilmington Journal) — In an extraordinary discovery, the 40-year-old case files of the prosecuting attorney in the two 1972 Wilmington Ten criminal trials not only document how he sought to impanel, according to his own written jury selection notes, mostly white “KKK” juries to guarantee convictions, but also to keep Black men from serving on both juries.

The prosecutor chose, in his own words, “Uncle Tom” types to serve on the jury, it was disclosed. The files of Assistant New Hanover County District Attorney James “Jay” Stroud Jr. also document how he plotted to cause a mistrial in the first June 1972 Wilmington Ten trial because there were 10 Blacks and two whites on the jury, his star false witness against the Ten was not cooperating, and it looked very unlikely that he could win the case, given the lack of evidence.

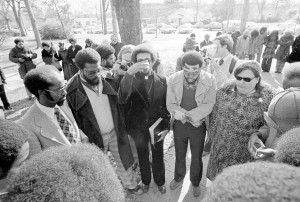

Members of the ‘Wilmington 10’ hold a brief communion service before boarding a prison bus on Feb. 2, 1976 in Burgaw, North Carolina, as they surrendered to start prison terms on convictions growing out of 1971 racial disorders in Wilmington, N.C. Four of the group shown from left are Connie Tindall, the Rev. Ben Chavis, Jerry Jacobs and Anne Sheppard.

History shows that prosecutor Stroud told the presiding judge that he had become “ill,” as that first trial began, and a mistrial was indeed declared. It was during the second trial, 40 years ago this week, that Stroud got a jury more to his liking – this time 10 whites and two Black domestic workers – and a different judge who was arguably biased against the defense.

The result? In October 1972, the 10 young civil rights activists, led by the Rev. Benjamin Chavis, were falsely convicted of conspiracy charges in connection with racial violence in the small North Carolina port city a year earlier. The nine Black males and one white female were collectively sentenced to 282 years in prison, some of which they all served before the three state’s witnesses recanted their false testimonies in 1977, admitting to being paid by prosecutors.

A federal appeals court, citing prosecutorial misconduct among other findings of fact, overturned all 10 convictions in December 1980. However, in the subsequent 32 years, the state of North Carolina has refused to follow suit, not allowing the Wilmington Ten – four of whom have since deceased – to clear their names.

The explosive “Stroud files,” as they’re being referred to, were discovered several months ago by a Duke University professor who was researching the Wilmington Ten case for a book he was writing.

When the Wilmington Ten Pardons of Innocence Project, a special outreach effort of the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA) to seek pardons of innocence for the Ten from North Carolina Gov. Beverly Perdue, announced its formation earlier this year, the professor allowed the Wilmington Journal and Carolinian newspapers, both NNPA members, access to the materials.

Some of the contents of the Stroud files are being revealed only now because attorney Irving Joyner, law professor at North Carolina Central University School of Law in Durham, NC; and attorney James Ferguson of Charlotte, the original lead defense lawyer for the Wilmington Ten, spent the summer confirming the authenticity of the materials.

On Sept. 5 during a forum at the law school on the Wilmington Ten case hosted by Prof. Joyner; Rev. Chavis; the Rev. Kojo Nantambu, a colleague who worked with Rev. Chavis in Wilmington in 1971 as they led a Black student boycott of the local racially divisive public school system; and Ms. Judy Mack, the daughter of now-deceased Wilmington ten member Anne Shepard, attorney Ferguson confirmed what he discovered in the Stroud files.

There was a fair amount of confirmation of things we suspected at the time that race was the central strategy of the prosecution,” attorney Ferguson maintained, singling out a legal pad that prosecutor Stroud used during jury selection of the first trial to track Ferguson’s questioning of potential jurors in Pender County, a neighboring county the case had been moved to in June 1972.

Pender had a larger African-American population than New Hanover, where the Wilmington Ten had been charged, thus, more Black candidates for jury service.

Ferguson details how Stroud wrote on the top of one page of his jury selection legal pad, “Stay away from Black men.” Next to that on the top of that same sheet, Stroud wrote, “Leave off Rocky [Point], Maple Hill. Put on Burgaw, Long Creek Atkinson Blacks.”

Apparently in Stroud’s mind, Blacks from the more rural towns of Burgaw, Long Creek and Atkinson, would probably be less likely to identify with “radical” civil rights leaders like Ben Chavis than African Americans from the more urbane towns of Rocky Point and Maple Hill.

Indeed, the 29th prospective juror on that same page named “Randolph” has a capital “B” in front of his name in the margin, and in parentheses the word “no,” and written afterwards, “on basis Maple Hill.”

In contrast, another possible juror, number 9 with a “B” named “Murphy,” Stroud has written in parentheses, “Worth chance because from Atkinson.”

There are several prospective jurors listed by name, and if not, certainly by number, who have the capital letter “B” written in the margin. If there was any doubt about the “B” indicating “Black” — which was attached to many names the words “leave off” were added.

On prospective “B” juror number eleven named “Graham,” Stroud writes, “knows; sensible; Uncle Tom type.”

On Number 27 named “Stringfield,” Stroud writes, “no named Black on jury.” On Number 19 named “James” Stroud writes, “stay away from,” apparently indicating that the potential juror is a Black male he doesn’t want.

And prosecutor Stroud had unmistakable codes for white jurors he preferred.

On that same legal pad sheet tracking juror interviews, when Stroud was impressed with a white interviewee’s answers, he’d write down the three letters of the alphabet most commonly associated with the most fear white supremacist group in the South at the time – the Ku Klux Klan.

“KKK?…good” is what Stroud wrote for juror Number 1 known as “Pridgen.” For Number 6 named “Heath,” the reverse, “O.K.” then “KKK?”. Number 75 on a subsequent page was “Fine — probably KKK!!” and on Number 99 Stroud writes, “does not have a record —KKK!!”

There are other potential white jurors Stroud has also written “KKK” next to, but he then crosses them out, possibly indicating that they were no longer eligible.

In some cases, Stroud apparently had trouble telling the difference between whites and fair-skinned Blacks. For Number 38, the prosecutor writes, “good name and location – KKK if white.” On Number 59, Stroud writes, “take off on basis of name if Black.”

After studying the notes, Attorney Ferguson observed: “Race infused the jury selection strategy in that June trial.” When the first jury was dominated by Blacks, Ferguson said,

“We were able to position ourselves in a way that we were headed towards getting what appeared to be a jury that might be fair. But at that time, as they say, a funny thing happened on the way to the forum.”

Ferguson and Prof. Irving Joyner note that on the cardboard back of that jury selection legal pad Stroud used, the prosecutor literally drew a line down the middle. On the left he titled it, “Disadvantages of Mistrial.” On the right, “Advantages of Mistrial.”

Ferguson quipped, “Most people don’t list the pros and cons of getting sick.”

Stroud, plotting his next move, noted, listed the disadvantages of a delay: “1 – waste of a week; 2- could affect Hall’s attitude and other witnesses (referring to star state’s witness Allen Hall, who was being paid by the prosecution to deliver false testimony) 3 – possibly waste of two weeks unless Allen can set up quick docket; 4 – inconvenience to all concerned; 5 – possibly get Judges Chess, Godwin or Copeland on new trial; and 6 – delaying getting cases over with.”

On the other side of Stroud’s list for “Advantages of Mistrial’ in the first Wilmington Ten trial, the prosecutor listed, “1 – different judge; 2 – better prepared to select jury and to handle motions/more organized; 3 – avoid longer jury selection and hung jury in Pender because of their concern about retaliation; 4- fresh start [with] new jury from another county; 5- avoid reversible error [and] new trial on lack of [defense] witness interviews; 6 – can enlist Dan Johnson’s help; 7 – opportunity to separate [white Wilmington Ten member Ann] Shephard (sic) from others to keep out [Allen] Hall’s letter; and 8 – time to have case well prepared and organized.”

Stroud decided to fake an illness, resulting in a mistrial.

“The main prosecutor in the case (Stroud) suddenly became ill,” Ferguson recalls. “For what reason I do not know. [Perhaps] sitting there looking at that many Black folks serving on the jury. But he became ill, sort of, and decided that he could not proceed with the trial. So that trial was aborted.”

Ferguson recalls how during the second trial in September 1972, not only did the new judge allow white jurors with apparent biases against the Wilmington Ten to be seated, but allowed state’s witness Allen Hall to jump off the stand to attack him without punishment, and disallowed any defense challenges to the prosecution’s case before the convictions.

The two Blacks who were seated on the second trial’s jury were a maid who worked in a white home, and a janitor, two “easy targets of economic reprisal,” said Ferguson.

“We complained throughout about the prosecution’s use of challenges to remove Blacks from that second jury,” Ferguson said. To no avail. In the end, the Wilmington Ten were convicted, and remain felons in the state of North Carolina until this day.

Former prosecutor James Stroud Jr., 69. could not be reached for comment on this story. According to published reports say Stroud lives in Gastonia, N.C. said to be homeless. The Gaston Gazette reported in December 2011 that Stroud, who went on to have a successful private law practice after prosecuting the Wilmington Ten, fell on hard times.

His adult son, Kirk told the paper that Stroud suffers from manic polar disorder, a diagnosis that reportedly goes back to when Stroud as starting law school more than 50 years ago. The Gazette said police reports show former prosecutor Stroud has been arrested at least 14 times in the past five years, with some of the charges ranging from assault with a deadly weapon, to several domestic violence protection orders, to a charge of hit and run.

Stroud’s son told The Gazette last December that his father, “…has yet to be involuntarily committed for mental health treatment.” He lost his license to practice law in North Carolina in 2008, according to the North Carolina State Bar.

(The Stroud file documents cited in this story, along with attorney James Ferguson’s presentation, can be see in the video, “The Wilmington Ten — the Stroud Files” on YouTube).

This article was originally published in the September 17, 2012 print edition of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper